America’s aging prison population is posing challenges for states

© Akarawut Lohacharoenvanich - iStock-1436012592

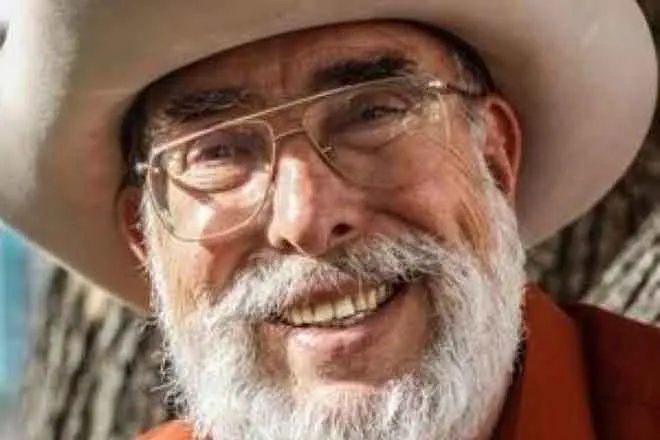

America’s prison population is growing older at a pace that some experts say is unsustainable. As of 2022, the latest year with available data, people 55 and over made up nearly 1 in 6 prisoners — a fourfold increase since 2000 — and their numbers are projected to keep rising.

A new report from the American Civil Liberties Union and the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin warns that this trend is straining correctional systems that were not designed to care for older adults.

If current trends continue, the authors estimate that by 2030 as much as one-third of the U.S. prison population will be over 50.

“It puts it into perspective how bad that this has gotten,” said Alyssa Gordon, the report’s lead author. Gordon is an attorney and legal fellow with the ACLU National Prison Project. “People don’t realize that prisons are woefully equipped to handle this crisis.”

The findings are based on data from public records requests to all 50 state corrections departments, publicly available state prison population datasets and the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Some data, however, were not available for every state, limiting the authors’ ability to make extended state-by-state comparisons.

The report’s findings come as states face competing pressures: a nationwide crackdown on crime and public safety, tightening corrections budgets and severe overcrowding and staffing shortages.

The aging prison population is largely a product of the “tough-on-crime” era of the 1980s and 1990s, when lawmakers at both the state and federal level enacted a wave of punitive policies under the banner of public safety, according to the report. These policies, including mandatory minimums, “three strikes” laws and “truth-in-sentencing” statutes, led to significantly longer sentences and fewer opportunities for early release. Experts say many of those policies remain in place today.

The report also highlights the growing price tag of incarcerating an aging population. Corrections spending data shows an upward trend in medical costs across some states, according to the report.

Prisons often lack accommodations for older adults, including accessible showers and beds, dementia care and hospice services, putting them at greater risk of injury or premature death, according to the report.

© iStock - turk_stock_photographer

Emergency protocols also are frequently inadequate, the authors found, leaving older prisoners particularly vulnerable during natural disasters, disease outbreaks and other emergencies.

Some experts say that the costs of incarcerating older adults could create common ground for policymakers, as reducing this population may lower prison spending without significantly affecting public safety.

“If you want to figure out which population to target where it doesn’t have a public safety implication, this is the population to turn to,” Michele Deitch, one of the report’s authors and the director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab, told Stateline. “This is an issue that can gather bipartisan support.”

The report’s authors estimate that more than half of incarcerated people over 55 — more than 58,000 individuals — have already served at least 10 years, with nearly 16,000 behind bars for more than half their lives.

Older adults are less likely to reoffend, with recidivism rates reported at 18 percent in Colorado in 2020, 12 percent in South Carolina in 2021, and 6 percent in Florida in 2022. These rates are far below the national three-year rearrest rate of 66 percent for the general prison population, according to the report.

In recent years, more states have explored measures to address the aging prison population, including legislation commonly called “second look” laws or policies that expand parole eligibility for older or seriously ill inmates.

Most recently, a new Maryland law, which is set to take effect on Oct. 1, will allow certain incarcerated people to apply for geriatric parole. The law applies to those who are at least 65, have served at least 20 years, are not sex offenders, are serving sentences with the possibility of parole, and have had no serious disciplinary infractions in the past three years.