Calling someone a 'jackass' is a tradition in US politics

When Virginia Democrat Sen. Tim Kaine called President Donald Trump a “jackass” in early February, Kaine engaged in a political practice that is as old as the nation.

Probably no animal is used more as an object of ridicule and derision in U.S. politics. Kaine’s epithet was hurled because Trump hadn’t shaken hands with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi before his 2020 State of the Union address.

Yet jackasses are so entangled in American political history that I must ask: Where would politics be in this country without jackasses?

Object of ridicule

While researching our forthcoming book, “The Art of the Political Putdown: The Greatest Comebacks, Ripostes, and Retorts in History,” my late collaborator Will Moredock and I found several references to politicians who responded to a rival’s insult by comparing them to the jackass, which is a male donkey, or sometimes the closely related mule.

The word jackass, or “male ass,” according to one etymologist, goes back to 1727. By the 1820s, it was commonly being used to describe a “stupid person.”

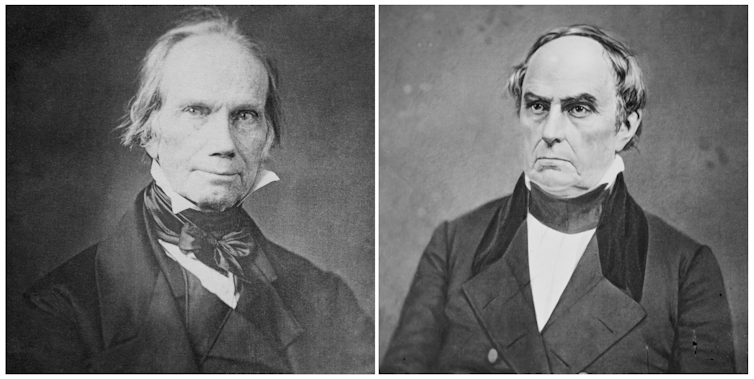

This was the intent of a retort in the 1820s by Kentucky congressman Henry Clay to Massachusetts Congressman Daniel Webster.

Clay was sitting outside a Washington, D.C. hotel with Webster when a man walked by with a pack of mules. “Clay, there goes a number of your Kentucky constituents,” Webster said.

“Yes,” Clay replied, “they must be on their way to Massachusetts to teach school.”

A connection with Democrats

In 1828, Andrew Jackson ran for president as the candidate of the new Democratic Party, which had been created from splintered factions of the Democratic-Republican Party.

Jackson, the blunt-spoken backwoodsman and war hero, was widely criticized as a “jackass” for advocating populist reforms.

He responded by using the image of the jackass on his campaign posters.

“Jackson embraced the image as the symbol of his campaign,” Jimmy Stamp wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “rebranding the donkey as steadfast, determined, and willful, instead of wrong-headed, slow, and obstinate.”

Jackson won the election, and the jackass first became associated with Jackson and the Democratic Party.

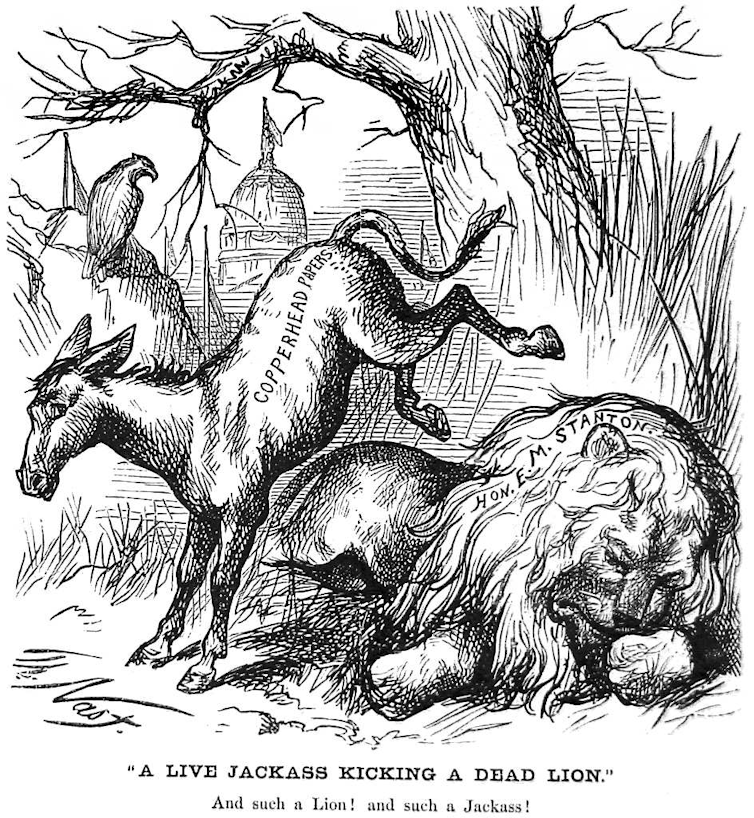

More than 40 years later, after the Civil War, a political cartoon really popularized the image of the jackass as the symbol of the Democratic Party.

In 1870, Harper’s Weekly published a Thomas Nast cartoon, “A Live Jackass Kicking a Dead Lion.” It depicted Northern Democrats, nicknamed “Copperheads,” attacking the recently deceased former Cabinet member Edwin Stanton, a lion of Radical Republicans.

The donkey – a more polite and gender-neutral word for “jackass” – became the symbol of the Democratic Party.

The word “jackass” remained a term of ridicule.

Twain defends the jackass

Critics such as Mark Twain thought comparing men and politicians, in particular, to jackasses was unfair to jackasses.

“Concerning the difference between man and the jackass: some observers hold that there isn’t any,” he said. “But this wrongs the jackass.”

Twain also defended jackasses in his 1894 novel “Pudd’n’head Wilson.”

“There is no character, howsoever good and fine, but it can be destroyed by ridicule, howsoever poor and witless,” he wrote. “Observe the ass, for instance: his character is about perfect, he is the choicest spirit among all the humbler animals, yet see what ridicule has brought him to. Instead of feeling complimented when we are called an ass, we are left in doubt.”

The jackass, however, remained a term of derision in American politics.

For instance, when Democratic Congressman Champ Clark of Missouri was speaker of the House of Representatives during the 1910s, an Indiana congressman interrupted the speech of an Ohio congressman by calling him a “jackass.”

Clark ruled the expression in violation of protocol, and the Indiana congressman apologized.

“I withdraw the unfortunate word, Mr. Speaker, but I insist the gentleman from Ohio is out of order.”

“How am I out of order?” the Ohioan asked.

“Probably a veterinarian could tell you,” the Indiana congressman responded.

The jackass revisited

Donald Trump’s presence in American politics has brought a resurgence in the word “jackass” – or at least the two things have happened simultaneously.

In 2015, then-presidential candidate Trump ridiculed the characterization of Arizona Senator John McCain as a war hero. McCain served more than five years in a prisoner-of-war camp during the Vietnam War.

In reply, U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, who also was seeking the GOP presidential nomination, called Trump “the world’s biggest jackass,” adding that even “jackasses are offended” by Trump.

Trump responded by making public Graham’s private cellphone number.

During the final weeks of the 2016 presidential campaign, MSNBC aired an interview with a conservative voter who said she would vote for Trump and the GOP – even if Trump was at the top of the ticket.

“I am voting for the conservative party,” she said. “And if this jackass just happens to be leading this mule train, so be it.”

The connection between Trump and the jackass appeared in greeting cards, too. The Canadian company OutLayer sold a Christmas card that said, “Trump is a jackass. Merry Christmas.”

One 2020 bumper sticker, however, uses the Democratic donkey to tout Republicans in the November election. “Don’t be a jackass,” it says. “Vote Republican.”

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]![]()

Chris Lamb, Professor of Journalism, IUPUI

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.