Commentary - An Army captain who refused orders in 1864 is remembered with reverence for his defiance

The Sand Creek Massacre comes to mind in reading about U.S. Representative Jason Crow, a decorated combat veteran from Colorado who declared that members of the U.S. military must refuse illegal orders.

“No one has to carry out orders that violate the law or our Constitution,” said Crow and five other members of Congress, all of them veterans of our armed forces or intelligence services, in a video posted last week.

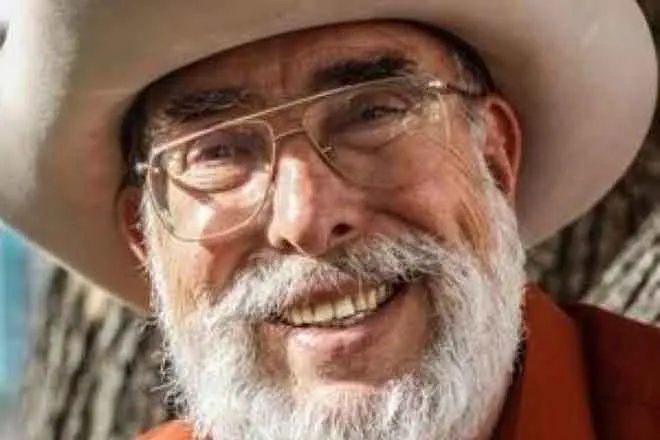

Jason Crow

President Donald Trump went ballistic, branding them as traitors. “HANG THEM GEORGE WASHINGTON WOULD !!” said a social media post that Trump shared. He later backtracked, saying he didn’t actually call for their deaths. Not sure what hanging short of death looks like. Crow and other legislators did report death threats.

Denver7 talked with a former U.S. Army officer, Joseph Jordan. His law firm specializes in defending service members under investigation. He cited the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which says service members must obey orders, unless they are “patently illegal,” such as one that “directs the commission of a crime.”

But the code says those who disobey orders risk facing a court martial. A military judge decides if an order was lawful.

Writing in the New York Times, David French, an attorney who served in Iraq, as did Crow, parsed details of the relevant federal law. Shooting a prisoner is unambiguously illegal, said French. Bombing a home that is thought to contain insurgents is not.

Looming large is the legality of Trump’s orders to kill those on boats in the Caribbean who may — or may not — be carrying narcotics. Trump, said French, “has put the military in an impossible situation. He’s making its most senior leaders complicit in his unlawful acts, and he’s burdening the consciences of soldiers who serve under his command.”

Captain refuses to kill

At Sand Creek, on Nov. 29, 1864, Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer refused to allow their men to participate in killing about 200 Cheyenne and Arapahoe natives, most of them women and children.

The Great Plains in 1864 were contested territory. Colorado had become a U.S. territory in 1861, but the Cheyenne and other tribes who had migrated over the previous 150 years to build lives around the plentiful buffalo herds were not consulted. Friction was growing. Murders had occurred.

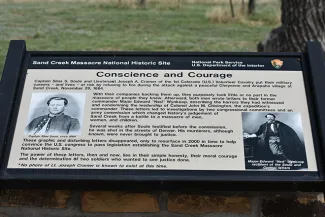

One of many signs at the Sand Creek Massacres National Historic Site calling out the history of the area and those involved. © Chris Sorensen

Desperate to figure out a co-existence, a delegation of Arapahoe and Cheyenne leaders had traveled to Denver that September. Colorado’s territorial governor, John Evans, was present but remained largely silent. The natives left, believing they had been assured safety if they remained in place in southeastern Colorado. About 350 of them and various other individuals were camped along the dry creek bed that November.

Colonel John Chivington had other ideas. He was a hero from an 1864 Civil War battle in New Mexico. He had been at the peace negotiations that September. But perhaps hoping to embellish his reputation and win a seat in Congress, Chivington set out from Denver for Fort Lyons, near today’s Las Animas. There, he detained anybody who he thought would interfere with his plans.

Marching overnight, Chivington and his men arrived at the Sand Creek encampment at dawn. The natives had hoisted the American flag amid their teepees, but it did them no good. A triumphant Chivington and his men returned to Denver hoisting scalps. They were welcomed as heroes.

Some saw them otherwise. Soule and Cramer, horrified by what they had seen, wrote impassioned letters to their commanding officer, Major Edward Wynkoop. The Army held hearings several months later. Soule did not live long enough to be fully vindicated. He was assassinated in Denver the next April. Both Soule and Evans are buried at Riverside Cemetery, north of downtown Denver.

Among many accomplishments, Evans helped found both Northwestern University in Illinois and the University of Denver. In 2014, both universities commissioned reports examining the culpability of Evans in the massacre. The Northwestern report was slightly more restrained, but both found Evans bore responsibility for helping create the circumstances. More than any other political official in Colorado Territory, said the DU report, Evans “created the conditions in which the massacre was highly likely.”

Soule’s grave is marked by a simple white tombstone along with other veterans. The grave of Evans is large and imposing. Last Memorial Day I found flowers, a flag and a testimonial at the grave of Silas Soule. Others had visited, too. As for the tombstone of Evans, I saw nothing. He had remained silent in 1864 when leadership was needed.