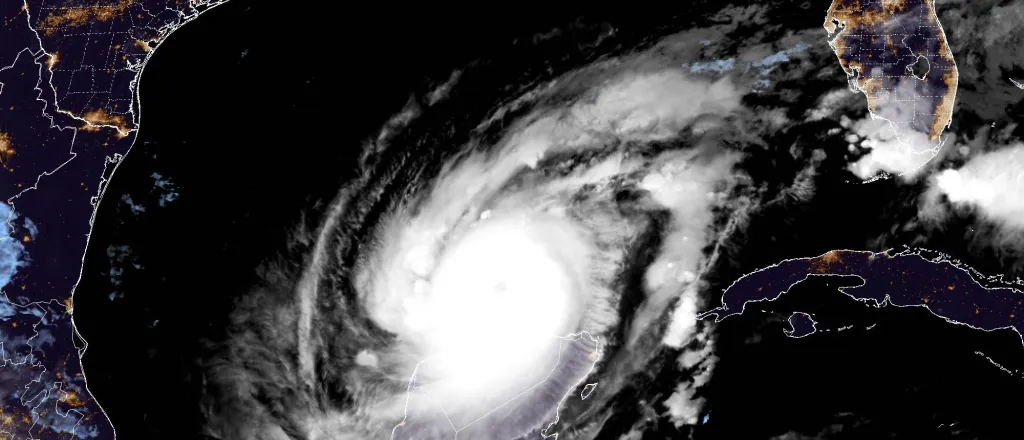

Commentary - Milton stirs memories of when Florida saw four storms in six weeks

Hurricane Milton - October 10, 2024 - NOAA

(Florida Phoenix) Here we go again — our second major hurricane in less than a month. Its climate change-fueled rapid intensification has been startling to watch. Its expected losses are staggering.

I hope you took this one seriously, despite the fact that it shares a name with a goofy character in the movie “Office Space.” One of my friends said hurricanes should have scarier names, like “Apocalypso,” “Catastrophia,” and “Insurance-Nightmaria.”

I’m writing this while evacuating before the storm. By the time you read this, we’ll know where Milton landed, how powerful it became and how much it messed up a Florida already reeling from horrible Helene.

If you’re like me, you’re having flashbacks to 20 years ago. They’re not the good kind of flashbacks, either. No groovy music or silly fashions.

In 2004, Florida was clobbered by a series of FOUR major hurricanes in just six weeks. One smart-alecky columnist (OK, it was me) described it this way: “The storms stomped across our landscape like a flamenco dancer wired on Red Bull, leaving quite a trail of destruction.”

Next came Frances, a Category 2. It hit Hutchinson Island, crossed the peninsula, swooped through the Gulf of Mexico, then came back ashore as a tropical storm in the Panhandle. Before it was done, it had caused 37 deaths in Florida.

The next one, Hurricane Ivan, crashed into Pensacola as a Category 3. It then circled back to drench South Florida as a remnant low. Between those two forays, it caused 14 deaths in Florida.

The last one, Jeanne, was a Category 3 when it slammed into Stuart on Sept. 25. Only three people died in Florida, but more than 3,000 died in Haiti.

“Since hurricane records started being kept in the 1850s, it was the only time that four storms hit the state of Florida,” a history by the Army Corps of Engineers noted. “It was also the first time since 1886, when Texas was hit, that four hurricanes had made landfall in the same state in one year.”

On top of the casualties, each storm did so much property damage that it could only be measured in billions-with-a-B. Instead of the Sunshine State, people were calling us the “Plywood State” because so many damaged buildings had to be boarded up.

“Nearly every square inch of Florida felt the impacts from at least one of those four storms,” the folks from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported in a 2019 essay on that mean season.

I wondered what, if anything, we learned 20 years ago that might be applicable to our current one-two punch. I contacted a bunch of folks who could answer that question.

The first person I heard back from was Jim Beever, who spent 16 years as a biologist for the state wildlife commission and then 17 years with the Southwest Florida Regional Planning Council. He told me something that — well, I will get to it in a minute, because I think it’s the bottom line for this year’s disasters too.

Later, Beever added that “other things we learned from 2004 hurricane season was how to live without air conditioning [and] how to barbecue everything in the freezer so it will keep.”

A little wind and rain

Part of the problem 20 years ago was complacency.

We’d experienced a stretch with no hurricanes that made landfall. As a result, when the warning went out about Charley, some people took the news about as seriously as they would a warning from Harry Potter about a unicorn stampede.

It didn’t help that the season got off to a slow start. The first named storm didn’t develop until July 31. But once Charley showed up — on Friday the 13th, no less — we were off on a rough ride.

The center of the forecast cone of uncertainty showed it heading to the Tampa Bay region, where everyone hunkered down. My wife and I cleaned out a coat closet for us and our two little kids to hide from the storm’s fury.

But then Charley took a sliiiiight turn to the south and hit Charlotte County, where the residents weren’t expecting it. They didn’t understand the “uncertainty” part of the cone’s name. They followed the line, not the shaded part of the map.

“A major hurricane had not made landfall in this region in 35 years, and many residents were new to the area,” the International Hurricane Research Center’s report on the storm noted. “There was a general lack of real hurricane experience, yet this area had been under numerous watches and warnings within the last several years. This resulted in a tendency to not take the messages seriously. Most reported expecting to get only a ‘little wind and rain’”

I’ve covered plenty of hurricanes from the field — including Hugo (Category 4) and Andrew (Category 5) — but for Charley I was assigned to rewrite. That means I stayed in the St. Petersburg newsroom and took calls from reporters in the field, then crafted their reports into stories of what happened.

Our reporter in Punta Gorda rode out the storm in Charlotte County’s emergency operations center, which lost its roof in the high winds, then in a stronger building at the county airport. When I talked to him, he sounded traumatized. He said he couldn’t describe Charley’s damage — the scope was too wide, the swath too broad.

“Let’s focus on what you see right in front of you,” I said, so he told me about that. Then we worked our way out from there. By the end of the call, he sounded better, or at least calmer.

We had no idea we’d be replaying this exercise three more times.

See you in hell

One of the folks I contacted this week was Wayne Daltry, formerly the “smart growth” coordinator for Lee County. I asked him what Southwest Florida learned from Charley and the storms that followed.

“First,” he told me, tongue planted in his cheek, “you and your closest friends pick a good watering hole to have a final toast, ‘See you in hell or on the other side of this storm.’ We did it four times that year.”

The more important lessons he mentioned include “ensuring that the state/federal road system was cleared as quickly as possible (or fixed, or bypasses quickly identified) and broadcast.” Ports, airports, and railroads are important to restart so they can begin bringing in supplies after the storm, he told me.

Daltry also mentioned needing “a quick system of accounting for people through various volunteer organizations … sponsored by the community.”

Then he mentioned one I hadn’t considered: “Make sure places for first responders’ families are identified and first responders take advantage of moving their exposed families to those places, so the first responder can actually worry about the job knowing the family is okay.”

He educated me on two key terms:

“Emergency Preparedness is the plan,” he said. “Emergency Response is carrying out the plans, tempered by experience and reality. The promise of recovery has to be immediate, and visible progress is required to keep the population believing and working together.”

The master of disasters

The person I was especially eager to hear from was the man who was in the hot seat for all four of these storms: former Governor Jeb (no exclamation point, please) Bush.

Bush was more attuned to hurricanes than any previous governor, because before he ran for office, he’d gone through Andrew.

He, his wife, three children, mother-in-law (and two Secret Service agents, thanks to his dad being president) rode out the storm at a friend’s house in Kendall. At one point, with the whole house shaking, everyone took refuge in an interior hallway. (Okay, NOW you can use that exclamation point.)

Bush never forgot that experience. When it came time for him to oversee the state response to hurricanes, he turned into a total storm wonk. Bush put in the time to learn what he needed to know about everything from residential building codes to how gasoline is pumped into Florida.

When I contacted him, he pointed out that Florida’s nightmare stretched beyond just 2004. Instead, it was “16 months dealing with 8 hurricanes and 4 tropical storms.”

In that time, he told me, “We learned that we needed to harden our special needs shelters, provide more support for public health nurses that took care of the vulnerable Floridians in the shelters, and provide generators to keep the power on.”

In addition, he said, “we learned that we needed to upgrade our evacuation strategies. We learned we needed to insist that gas stations have generators on evacuation routes.” Speaking of which, “we learned we needed to pre-stage generators to keep water and wastewater systems operational.”

He mentioned that he felt “fortunate to work with so many talented people.” One of them was W. Craig Fugate, who served as head of Florida’s emergency management agency. He did so well as our Master of Disasters, President Barack Obama named him the boss of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Fugate is remembered by the public today for creating the “Waffle House Index” for disasters, one that can be concisely stated as: “If you get there and Waffle House is closed, that’s really bad!”

He was his usual ebullient self when we talked on the phone. The main lesson of 2004, he said, was “be nimble.” To do that, he had to focus on one thing: “What do we need to do to keep people alive?”

With the string of four storms, he said, “you’ve got to keep hitting the reset button.” Hurricane work has two stages and Florida had to keep toggling between the two: “evacuation” and “search and rescue.”

The key, he said, is “get in and get ’em stabilized. Once you get the power back on, that takes care of some of it.” But the main thing to remember from 2004 is this: “You can never anticipate having just ONE disaster.”

Before we hung up, he told me, “Keep watching the Waffle Houses!” I should note that lots of Waffles Housesclosed before Milton’s landfall.

There’s a much bigger issue here, though — one lesson we should have learned in 2004 and did not.

Not supposed to be permanent

Here’s the most important thing that Beever told me when I asked what we learned from the 2004 hurricane season: Zilch. Zip. Nada.

We didn’t learn a thing, he said.

“From what I observed in southwest Florida and in state government, very little if anything was learned,” Beever told me. “Both still approved every coastal development. While some municipalities planned and did projects for future storms, most did not.”

Fugate disagreed, talking up the efforts to “build back better” with tougher (and more expensive) building codes. “When the infrastructure is done better,” he added, “then the restoration times are lower.”

However, even he made an exception for Florida’s barrier islands. Building there seems foolish because they’re supposed to move back and forth with the waves like Muhammad Ali bobbing and weaving in the ring.

“Nature doesn’t intend for them to be permanent,” he told me.

Yet we’ve let money-mad developers run wild on the barrier islands in the past 20 years, cramming in so many homes and condos that proper evacuation is impossible.

Back in 2004, we had the Florida Department of Community Affairs in charge of planning communities. One of its jobs: To ensure evacuation times from flood-prone zones known as Coastal High Hazard Areas would take less than a day. The law said the development density in those areas should not make the evacuees need more than 16 hours to get away from a Category 5 storm.

But when Rick “I’m So Rich I Should Be President By Now” Scott became governor, he and the Legislaturekilled the planning agency with all the care and consideration of a beachgoer slapping at a noisy mosquito.

Now there’s no one to stop local governments from allowing their campaign contrib— er, excuse me, constituents — to build more and more development in those Coastal High Hazard Areas. Thus, evacuation times have been getting worse, making life on those islands more dangerous.

How dangerous? In Lee County, it’s now 96 hours, or 80 more than it should be. Two years ago, one Lee County official said that 35 other coastal counties were just as bad.

When Hurricane Ian hit there, it killed 72 people in Lee, some of whom probably would not have died if we hadn’t built homes where we should not have.

When you’re reading about the casualties from Helene and Milton and whatever silly-named disaster comes next, think about this. Think about how many of those folks paid the price for us not learning the things we should have figured out 20 years ago.

Maybe we should call the next storm “Developmentkillsusmania.”

Florida Phoenix is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Florida Phoenix maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Michael Moline for questions: info@floridaphoenix.com. Follow Florida Phoenix on Facebook and X.