Curious Kids: How are books made?

Lara Farina, West Virginia University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

How are books made? Julia, age 10, Petoskey, Michigan

Books are material things – usually made of paper, ink, thread and glue – but a lot of work goes into making them before they get assembled into something you might find at a library or bookstore. Most of this work has to do with a book’s content, the writing and art on its pages.

Cooking up ideas

Book authors usually begin the writing process by brainstorming ideas. They write down a number of thoughts and make notes about things they’ve observed or read.

Authors writing a made-up story, called fiction, might imagine the possible characters’ personalities and habits. They might also outline a plot, or the sequence of events that will happen in the story.

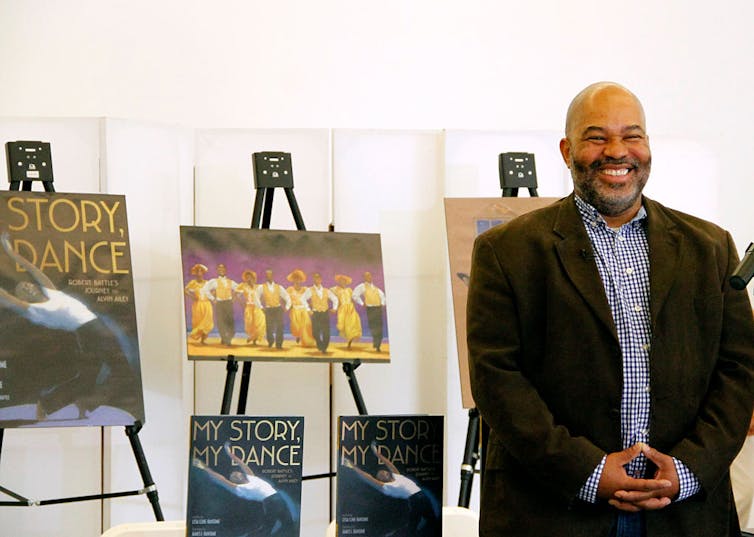

An author who is writing nonfiction – like history or science – will research the topic and decide how to interpret what they find. The research may involve looking at archival documents, interviewing people or visiting locations where important events happened.

Once authors have ideas about what they want to write, they need to think about whom they’d like to read their book. If, for example, an author is writing about outer space for a general audience, it’s important to explain the science in way that everyone can understand. An author who is writing for other astronomers who already know a lot about the subject shouldn’t spend much time explaining the most basic things.

Revise, revise, revise

After authors have brainstormed, researched, plotted and outlined their projects, they draft and revise. Few authors write something down once and never change what they’ve written. Most write a first or rough draft and later change many things, from the order of topics to the particular words they use.

When authors need to make these tough decisions about what to change, they may have the help of an editor. An editor’s job is to review drafts of a proposed book and help the writer make it as good as it can be, and to coordinate all the steps to publish the book.

Editors work for publishers, the companies that help create the final form of the book and then distribute, advertise and sell it. When writers want to work with an editor, and hope to turn their story into a real book, they send their revised draft to publishers in hopes that the company will purchase it. This way, authors get paid for their writing, but the publisher also profits from book sales.

Many other people work at a publishing company, too. Copy editors and proofreaders check for mistakes in an author’s writing. Designers and typesetters are responsible for the look of the book, including its cover. Publishers may also find illustrators for a book, although many authors want to illustrate their own.

The final steps

When the content of a book is all ready, it will be sent to a printer to be inked onto paper, glued or sewn together as a collection of pages, and bound into hardback or paperback copies. Hardbacks are books with stiff cardboard bindings and paper dust jackets to protect the covers. Paperbacks have a cover of only thick paper and are cheaper to make.

The first printing of some kinds of books, like novels or histories, is often a hardback. If lots of people want to buy the book and the publisher prints another batch of books – called a print run – they will typically be paperbacks.

So far, I have described the way that most books are made now. But book creation predates modern publication, printing and even paper. For many centuries, books were written by hand on vellum, which is made of animal skin.

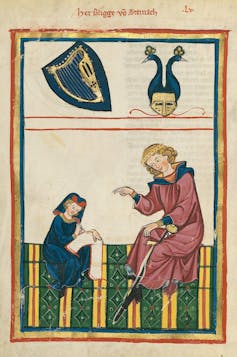

Before the invention of the printing press around 1440, most writing was done by scribes, artisans who were trained to write in special scripts called calligraphy. Authors could recite their work aloud to scribes, and the scribes would write it down. Scribes also copied a lot of material from other books to make new books for patrons, readers who told scribes what they wanted in a book and paid for it.

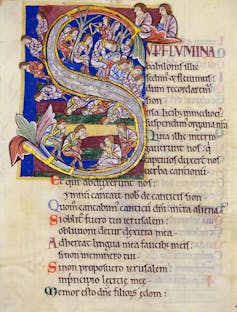

In my work as an English professor, I study many of these medieval handwritten books, called manuscripts. Often, manuscripts can give modern readers an idea of what particular people in the past wanted to read. For example, a book written for a queen might contain the stories she liked, calendars of important dates, a history of her family or her country and prayers and poems she might recite. There’s a good chance that the queen’s book was unique, because it was written specifically for her.

You can look here at pages from a manuscript made for use by one particular woman: Christina of Markyate, a holy woman in 12th-century England. She ran away from home as a teenager to become a recluse and later became a spiritual adviser to the monks of St. Albans monastery. The monks made this very beautiful book of prayers for her.

You can make your own mini-book just by folding a single piece of paper. Think of some content, write a draft and then be your own scribe by writing and illustrating your book!

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.![]()

Lara Farina, Professor of English, West Virginia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.