Curious Kids: Why are there prisons?

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why are there prisons? – Andrew H., age 8

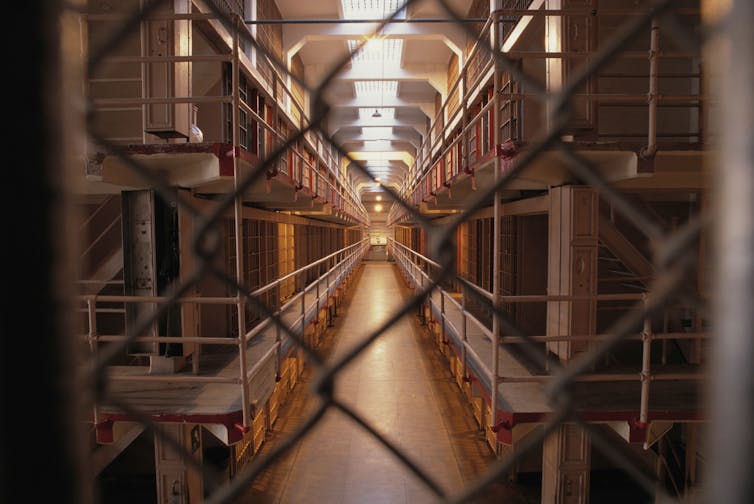

When people are found guilty of committing a crime, a judge will decide how they should be punished. Sometimes they are allowed to live in their own homes and they have to pay a fine or serve their communities, but sometimes they are incarcerated, which means they are ordered to live in a jail or a prison. During this time, they cannot leave and they have to follow the rules of the facility.

Jails and prisons are called correctional facilities because they are meant to help correct the person’s behavior so that person does not commit any more crimes. But as a criminologist – someone who studies crime and prisons – I often wonder how people decided that incarceration was a good way to “correct” people.

There is a long history of using jails and prisons as punishment for breaking the law, and to keep communities safe. But there is also debate about how well those systems work, how fair they are and how to improve them.

Jail vs. prison

Although jails and prisons are similar, they usually have different purposes. Most of the people living in jail have not been convicted of a crime yet and are waiting for the court to decide if they are guilty. A person who is found guilty can be sent to live in the jail as punishment, but they typically stay for less than one year.

If the judge sentences someone to be incarcerated for a longer period of time, that person is normally sent to a prison in another part of the state. Sometimes the prison is far away from their home, and it can be difficult for their families to visit.

Prison then vs. prison now

In the past, people were not sent to jails and prisons as a legal punishment. Instead, these places were used to contain people who were suspected of a crime, to keep them from escaping before their punishment was decided.

If they were found guilty, sometimes they were punished with physical pain, such as being whipped. Sometimes they were forced to work without pay or for very low wages. Others might be sent far away from their communities and not allowed to come back. The most serious punishment was execution, and many people were killed for their crimes.

Over time, most countries decided that these types of punishment were cruel or ineffective, so they started using jails and prisons as places where people could be punished by losing their freedom for a specific amount of time. Judges could give some people longer sentences if their crimes were more serious, and shorter sentences if their crimes did not deserve a long punishment.

People expected that some prisoners would learn a lesson from their prison experience. If they were scared of going back to prison, hopefully they would be less likely to break the law in the future. Some prisons tried to “rehabilitate” people by giving them an education, job training or therapy that might help them prepare to return home.

Longer sentences

In the 1970s, there was an increase in the number of crimes reported in the United States, and many people were scared. They thought that society would be safer if more people were sent to prison. The size of the prison population increased from around 200,000 people in the 1970s to around 2 million people in recent years.

People started spending very long periods of time in prison, and more people were given life sentences, meaning that they could never return home. Before, those punishments had been reserved for very serious crimes, but new laws passed during this time made them more common.

Prisons became overcrowded, which spread resources more thinly, including programs to help prisoners prepare to return to society. More people wound up committing crimes again after they returned home.

Improving prisons

People who study correctional facilities, like me, have found many problems to fix. Some have to do with the large number of people in prisons. Many nondangerous people wind up serving time there, when they could serve a different punishment and receive therapy in their communities instead.

Another major problem is racial discrimination. Many researchers have found that Black, Hispanic and Native American people are more likely to be sent to prison than people from other racial and ethnic groups, even if they were convicted of the same crimes. This can cause a lot of serious problems for their families and communities.

Societies might always need to incarcerate some people who have committed serious crimes or who pose a danger to others. Perhaps the system can become safer, fairer and more successful in punishing crimes while rehabilitating.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Joshua Long, Assistant Professor of Criminology and Justice Studies, UMass Lowell

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.