How to build wildfire-resistant communities on the wildland fringe

Jeanne Homer, Oklahoma State University

Across the West, thousands of people are deciding what to do about homes that have been destroyed by wildfires in recent months. Those planning to rebuild will be looking for ways to make their new homes and neighborhoods as fire-resistant as possible.

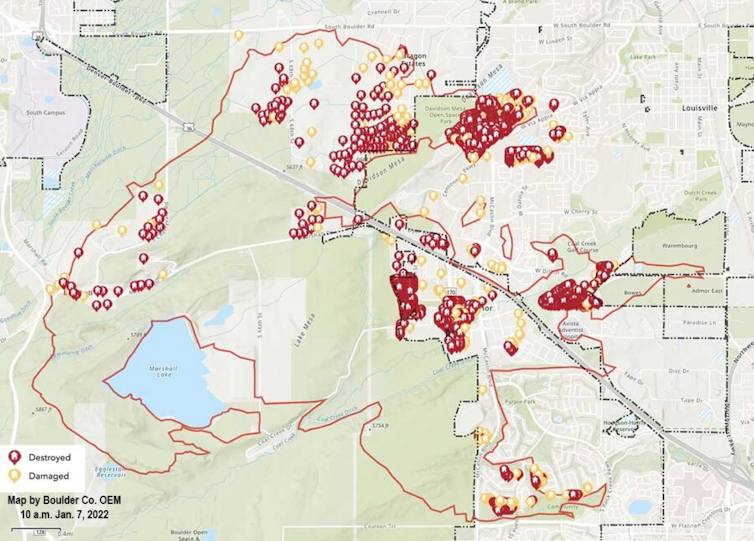

As an architect, I can tell you that rebuilding the same number of structures and replacing belongings after December’s Boulder County, Colorado, fire alone will likely cost more than the estimated US$513 million in residential losses.

To protect these investments as fire risk grows, here are some key strategies that communities and anyone building in the wildland-urban interface need to consider. Research shows that every $1 spent on prevention can save at least $6 in emergency rescue and recovery later.

Know the risk and plan for it

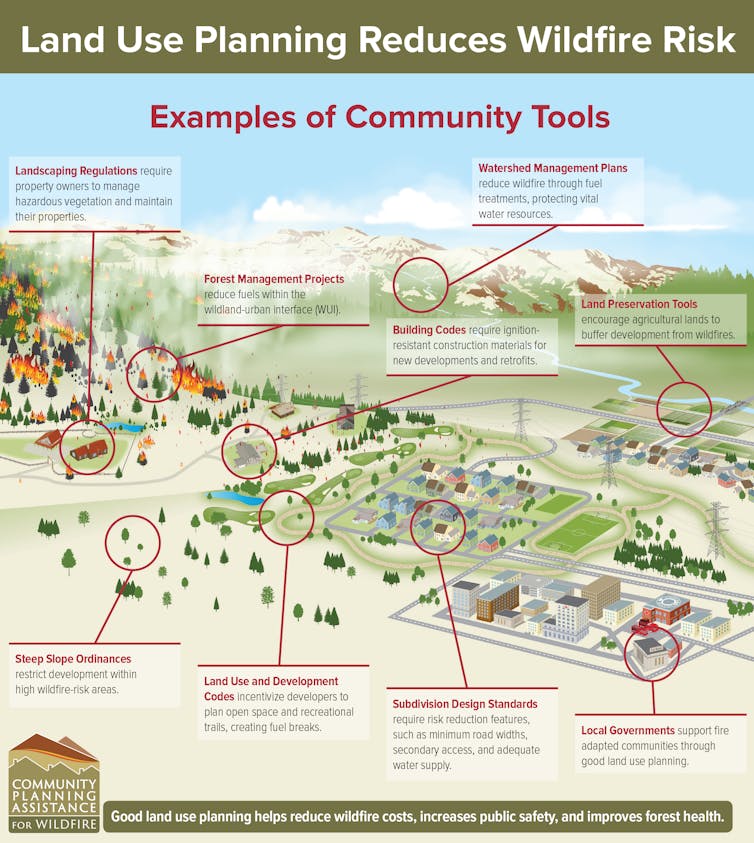

Designing for resiliency starts with risk assessments, particularly for communities in the wildland-urban interface – areas at the edge of forests and grasslands that are typically at higher risk of wildfires. Nearly half of Colorado residents lived in these areas in 2017, according to the Colorado State Forest Service.

From these risk assessments, communities can strategically plan and design safer developments.

California has a statewide code for its wildland-urban interface areas that includes details such as how far trees and shrubs should be kept away from homes, and construction materials to use that can help protect homes within a fire hazard zone. Typically, builders must follow these codes to get permits for the construction of certain buildings and neighborhoods in the risk areas.

Not all states provide that guidance, though. Colorado lawmakers rejected recommendations for a statewide code in 2014, leaving wildland-urban interface decisions to each county. Some Colorado communities and counties, including Boulder County, do require fire mitigation measures in wildland-urban interface areas. The International Code Council and National Fire Protection Association publish wildland-urban interface fire codes that can be adjusted to local conditions.

In a fire spread by extreme winds like the Boulder County fire, even following code may not be enough to save homes, but following that guidance in many circumstances will better protect a community.

Creating defensible space

Creating resilience in the wildland-urban interface involves several layers of defense.

At the community level, forest management, including thinning forests around communities and clearing away brush that could fuel a fire, is an important aspect of fire risk reduction and has become a priority for the federal government.

Carefully planning how land is used in communities can lower the risk to homes and property. A site’s vegetation types, weather and wind patterns, and slope of the ground can all affect how a fire spreads. Planning also ensures firefighters have road access to reach homes in all weather and identifies water sources for firefighting.

At the neighborhood scale, fire experts recommend maintaining an open area around housing developments in wildland fire-risk areas that is clear of tall grass and dense trees. These buffer zones could include mowed recreation fields, shopping area parking lots or other features that can slow a fire’s spread.

Depending on the fire risk, each house should have a perimeter of defensible space extending out at least 30 feet and as much as 100 feet from the home. Within this area, landscapes should be maintained in a way that reduces the chances of a wildfire spreading to the house and adjacent structures. That means keeping trees and shrubs separated from structures like the house, barn or garage, as well as from other landscaping. It’s best to avoid more combustible landscaping like conifer trees, and grass should be mowed and kept free of debris, such as dead leaves and branches that could catch fire.

The closest 5 feet around a house should be totally free of trees and debris, bushes, wood mulch, furniture, barbecue pits and grills – basically anything that can be ignited by flames, embers or radiant heat. Decks, fences and other projections can be built with non-combustible material or wood treated with fire retardant.

How to make construction fire-resistant

The last line of defense to reduce flammability and fire spread is the design of the house and its construction.

A simple shape with few projections and indented corners has been shown to be more resilient because there are fewer areas that can catch debris.

Most codes and the insurance industry suggest the roof be made of fire-resistive Class A materials, such as asphalt shingles or concrete tiles. The walls should be a continuous fire-rated construction from the foundation to the roof, and its assembly of materials, like wood studs, insulation, gypsum board and siding, should have undergone regulated testing. These assemblies of materials are rated based on the duration of time they can withstand fire.

Vulnerable openings like windows and doors should also have rated assemblies. And vents, if required for a particular climate, should be protected with fine mesh screens made of metal that can block most blowing embers.

Gutters and downspouts should be made of non-combustible materials – metal rather than vinyl – and be regularly cleaned or covered with a metal leaf guard. If possible, gutters can be eliminated with the addition of an underground drainage system to direct water away from the foundation and wall, but those systems also need maintenance.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Ideas for the future

These are all passive measures – they don’t need to be activated in an emergency, but they should be in place well before a fire event.

Researchers are also testing the performance of active systems for use in imminent threats, such as exterior sprinklers that don’t require electricity, large fire blankets that can cover a house, and fire-retardant foam that can be sprayed on structures.

With thorough risk assessment and several lines of defense, neighborhoods can be safer. But these strategies will have to be balanced with initial and long-term costs, realistic maintenance expectations and efforts to mitigate future anticipated threats. As storms become more intense and wildfires more frequent, we should be designing to reduce risk and our impact on the environment.![]()

Jeanne Homer, Associate Professor of Architecture, Oklahoma State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.