How the crisis in container ships could ruin Christmas

Stavros Karamperidis, University of Plymouth

Ningbo-Zhousan may not exactly be a household name, but find something in your house made in China and it’s quite likely it was delivered from there. Ningbo-Zhousan, which overlooks the East China Sea some 200km south of Shanghai, is China’s second-busiest port, handling the equivalent of some 29 million 20-foot containers every year.

At the time of writing, it has more than 50 ships waiting to dock. This is because the Ningbo-Meishan terminal, which handles about one fifth of the port’s total volumes, has been closed for a week after a member of staff tested positive for COVID. With still no word of a reopening, many more ships have diverted to alternative ports.

Unfortunately, this is the tip of the iceberg in shipping. China has eight of the top ten busiest ports in world, and they are running at well below normal capacity because of COVID restrictions. From Shanghai to Hong Kong to Xiamen, ships are in long queues to unload – and the diversions from Ningbo will be making this worse. The US west coast is also seeing bad congestion, with many ships anchored in California’s San Pedro Bay, awaiting access to the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

This has driven the cost of shipping rates for containers through the roof in recent weeks. The cost of moving a 40-foot container from China to Europe is currently running at around US$14,000 (£12,000), about ten times what it would normally be. So how long will this continue, and what will be the knock-on effects?

The pandemic and other problems

This situation is noticeably different to 2020. COVID restrictions had weakened the cargo-handling capacity of ports then as well, but it was less of an issue because global demand for consumer products was so much lower earlier in the pandemic. Now that many countries have vaccinated large numbers of people and their economies are reopening, demand has bounced back with a vengeance, and ports are not coping well.

On top of that have been other problems, not least the Suez Canal blockage in March. With ships stuck for a week after the huge Ever Given container ship got stranded, they were under more pressure than usual to return to Asia after they finally reached their destinations in Europe and the Americas. As a result, many didn’t wait to be fully loaded with empty containers.

This contributed to a lack of shipping containers in Asia, which was already becoming an issue because of ships not always calling in at their usual ports during the pandemic because demand was much lower than normal. The upshot is that containers have become more expensive, which has forced shipping companies to charge higher freight rates to cover the cost.

At the same time, weather has caused problems over the summer. Both the southern Chinese port of Yangtian and part of the port of Shanghai have spent periods closed in recent weeks because of typhoon alerts. The backlog has also been worsened by major importers baulking at the shipping costs and chartering their own ships instead. Home Depot, the big US home improvement retailer, did this in June for instance.

The future

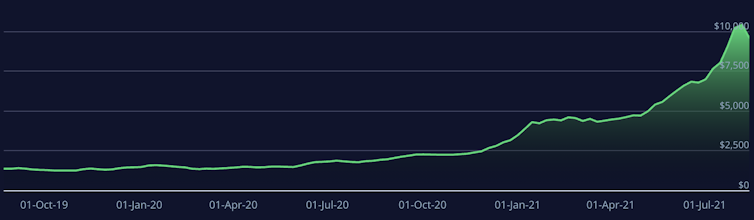

There has actually been a slight decrease in shipping rates in the past ten days, which has seen the Freightos Baltic Index fall from US$10,380 to US$9,568 per 20-foot container. But this is nothing to get excited about.

It broadly reflects the fact that the price of shipping goods from China to the US has come down after many ships diverted to that route to make the most of the high prices. Other routes, such as China to Europe and Europe to the Americas, are still mostly going up in price.

Freightos Baltic Index

As to whether this will continue, it is extremely difficult to say. Some freight companies have ordered new container ships to help address the shortage, but these vessels take two or three years to build so that is not going to make any difference in the short term.

What matters is future COVID outbreaks and to what extent China and other major port nations have to impose tough regulations to protect their populations. Perhaps we will be lucky and the situation will steadily improve from here, or perhaps this mismatch between supply and demand will endure for several years.

In the meantime, we can expect inflation to rise as importers pass on the costs of shipping to customers. Given that governments and central bankers were already worried about rising inflation for various other reasons, they could do without this extra dimension.

If the problem with shipping rates looks like enduring, it is also likely to feed into boardroom discussions about whether it is wise to rely so heavily on China as the manufacturing hub of the world. With relations between China and the west already at a low, and much talk of globalisation giving way to regionalisation, many are already arguing that they should make more consumer goods closer to home – “nearshoring”, as it is known in the trade.

But more imminently, one big issue will be putting the fear of God into retailers: Christmas. All those ships that diverted from their usual China-Europe route to help serve the US are cutting it fine to get back to China in time to restock. The crossing takes about 45 days, and they need to then leave China by about mid-October to make the 35-day crossing to get goods to Europe in time for December. If there is still congestion at the Chinese ports by October, this may not be possible.

The longer that this shipping crisis continues, the more that Christmas will be in trouble. It could become a huge news story in the weeks ahead as everyone looks forward to a “normal” festive season and many retailers desperately need a strong Christmas 2021 to help make up for what they lost from COVID restrictions.

If only an old man in a red suit with a sleigh could really take care of everything, we could all breathe a sigh of relief.![]()

Stavros Karamperidis, Lecturer in Maritime Economics, University of Plymouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.