How evangelicals moved from supporting environmental stewardship to climate skepticism

Neall Pogue, University of Texas at Dallas

White conservative evangelicals, who make up most of the religious right movement, largely oppose government regulation to protect the environmental initiatives, including efforts to curb human-caused climate change. Multiple social scientific studies, for example, consistently reveal that this group maintains a significant level of climate skepticism.

Contrary to popular perception, however, this hasn’t always been the case.

My research reveals how white conservative evangelicals supported an environmentally friendly position from the late 1960s to the early 1990s.

Christian environmental stewardship

In 1967, the idea of environmental protection became an issue for the wider Christian community after historian Lynn White Jr. published “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis.” The article argued that growing environmental degradation was the result of Christian philosophies that encourage society to regard nature as a simple resource for the sole benefit of humanity.

One of the many Christian thinkers responding to White included popular conservative evangelical author Francis Schaeffer.

To answer White’s accusation, Schaeffer took to the lecture circuit to convince audiences of the importance of Christian environmental stewardship. According to this perspective, all of creation needed to be treated with respect and not abused for economic benefit. He argued that humans must value the nonhuman natural world because it was created by and owned by God. Consequently, humans were only caretakers, custodians or stewards of the natural environment.

Perspectives of evangelical leaders

In 1970, the same year as the first Earth Day observance, which signified the birth of the modern environmental movement, Schaeffer’s perspectives were published in his book “Pollution and the Death of Man: The Christian View of Ecology.” Subsequently, Schaeffer’s environmental views became the standard environmental position among many conservative evangelicals for roughly the next 20 years.

Schaeffer’s ideas were reflected and expanded in major publications such as Christianity Today, the National Association of Evangelical’s United Evangelical Action and the Moody Bible Institute’s Moody Monthly.

As I continued researching this topic, archival documents revealed that in 1971, the Southern Baptist Convention conducted a poll reflecting the environmental views of its 12 million members. It found that 81.7% of pastors and 76.3% of Sunday school teachers surveyed believed that churches should lead efforts to solve air and water pollution problems.

In another example reflecting Schaeffer’s views, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Christian school textbook publishers included environment-friendly philosophies in material sold to parents, pastors and teachers who were helping expand the growing home-school and Christian school movement. The two most popular publishers, ABeka Book and Bob Jones University Press, both supported Christian environmental stewardship views. ABeka Book, for instance, lauded the efforts of preservationist and Sierra Club founder John Muir in a reader intended for sixth graders.

Respect for creation

The religious right retained its eco-friendly philosophies after the formation of its first official organization, the Moral Majority, in 1979. ABeka Book reprinted Muir’s story in 1986 and, as late as 1989, the publisher released an economics textbook that praised capitalism while warning of the environmental dangers of the free market.

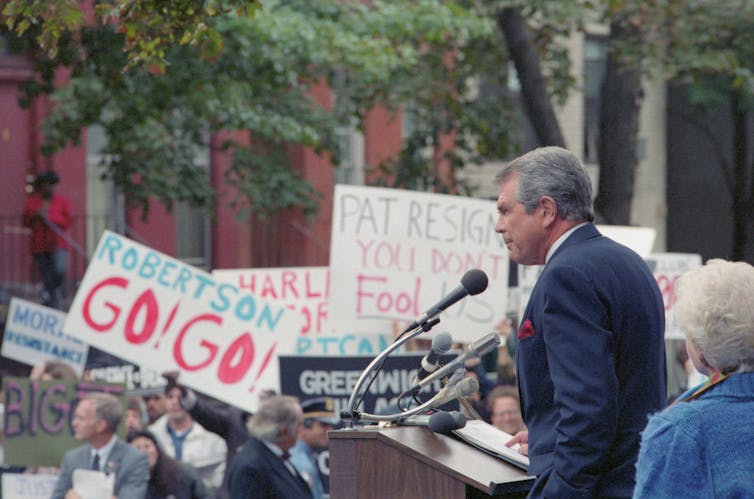

After bowing out of the presidential race in 1988, well-known televangelist Pat Robertson addressed the GOP National Convention in New Orleans. During his speech, he not only stated his support for classic religious right positions, such as traditional family values, but also restated the community’s eco-friendly views, saying that he hoped for a future “where the water is pure to drink, the air clean to breathe, and the citizens respect and care for the soil, the forests, and God’s other creatures who share with us the earth, the sky and the water.”

On a politically charged national stage, Robertson reprised Schaeffer’s views of Christian environmental stewardship, emphasizing how all creation should be respected.

While Christian environmental stewardship became an accepted environmental perspective within the religious right, it existed only as an idea or philosophy – not as part of organized activism. But the reality of this support, however, challenges past understandings that this community largely ignored or opposed environmental protection efforts.

The anti-environmental campaign

In the early 1990s, segments of the religious right tried turning eco-friendly philosophies into action. The Southern Baptist Convention held an environmental seminar in 1991 at which Schaeffer’s Christian environmental stewardship views were repeated. This effort, however, faced an insurmountable obstacle.

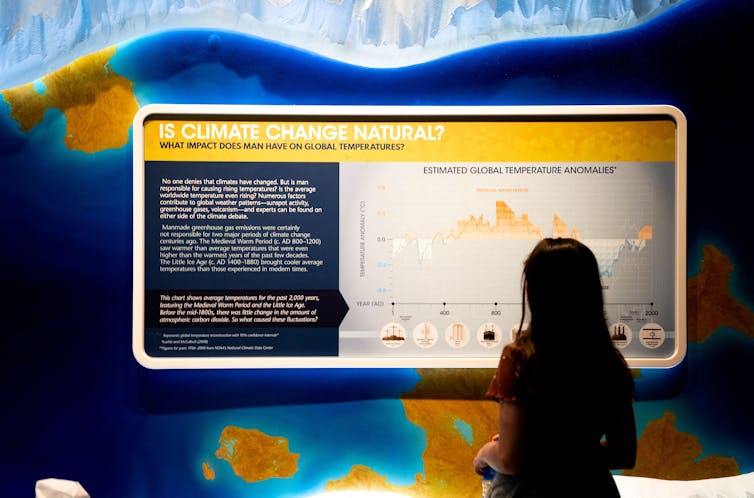

In an attempt to crush increasing international cooperation to address human-caused climate change, U.S. political conservatives launched an anti-environmental campaign. Conservative think tanks and special advocacy groups denied the reality of human-caused global warming, and some even supported conspiracy theories alleging that environmentalists wanted to create a one-world government.

Besides finding an audience in secular conservative Americans, these outreach attempts found a home among the traditionally politically conservative religious right supporters.

Anti-environmental messages increasingly relied on ridicule, which some leading pastors endorsed. Jerry Falwell, one of the founders of the religious right movement, for instance, began calling environmentalists “tree huggers” as early as 1992. At Pat Robertson’s Regent University’s newspaper, political cartoons mocked sympathy for the environment as left-wing extremism.

By 1993, the idea of Christian environmental stewardship had all but disappeared from the rhetoric of the religious right. In its place emerged firm opposition to environmental protection efforts, including the denial of anthropogenic climate change, which the majority of this community supports today.

Although religious right supporters largely reject Schaeffer’s Christian environmental stewardship today, a small but noticeable number of voices within the community are keeping it alive. Perhaps the largest eco-friendly organization is the Evangelical Environmental Network, which originated in 1993. Other notable developments include the signing of the Evangelical Climate Initiative in 2006 by well-known religious leaders.

These are remarkable developments that often employ theological arguments to support environmental activism. But they are largely overshadowed by the continuing nontheological anti-environmental arguments founded in misinformation.![]()

Neall Pogue, Assistant Professor of Instruction, University of Texas at Dallas

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.