Nebraska veterans justice diversion program defunded, delayed until at least 2027

Nebraska was set to lead the way July 1 with a new statewide criminal justice diversion program for eligible veterans through evidence-based treatment and case plans. But lawmakers delayed the rollout for two years in the face of growing budget woes.

It’s not yet clear whether Nebraska lawmakers can meet that later timeline and find the roughly $4.7 million in annual funding the state court system says is needed to start by July 1, 2027.

Several current and former state lawmakers called the funding decision “disappointing” and “incredibly problematic.” Another former lawmaker said she wasn’t in a position to “second guess” a response to the state’s fiscal situation.

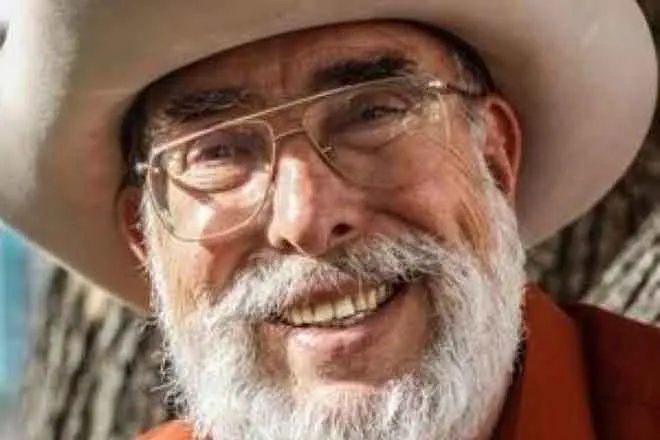

Former State Sen. Tom Brewer, the sponsor of the 2024 bill who represented north-central Nebraska, said in a May text that lawmakers had made a “conscious decision” to ignore veterans’ problems and wait to support those who have stumbled and need a second chance.

Brewer said the budget had already passed by the time he learned about the proposal.

“I believe that veterans will come with a vengeance against those senators and the governor if they take a law that was debated and voted on and made into law and then ignore it for their convenience for the budget,” Brewer said in May.

Unlike the state’s four specific Veterans Treatment Courts operating in the three most populous counties and in central Nebraska, the new veterans justice program would support all veterans, not just those who were honorably discharged. The Veterans Administration can’t reimburse the treatment costs for veterans who are dishonorably discharged, which increases state costs.

‘Playing politics with our veterans’

Two other lawmakers, both lawyers, joined Brewer this week in criticizing the spring decision as a continuation of not fully supporting veterans who have come home from serving.

“It’s unfortunate that we’re playing politics with our veterans,” former State Sen. Justin Wayne, the then-chair of the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee who partnered with Brewer on the bill, said this week.

“We don’t uphold our end of the deal, and those folks are left holding the bag,” said State Sen. George Dungan of Lincoln, another supporter of the law who works in the public defender’s office in Lancaster County.

This week, just before Veterans Day, Brewer added: “I think that they’re forgetting a group of folks that shouldn’t be forgotten.”

The law, passed 44-0 in April 2024, directed the Nebraska Judicial Branch to provide targeted statewide support to eligible veterans if a veteran’s military service-connected conditions contributed to their alleged criminal actions.

“The ones that are struggling are the ones that have seen some of the worst action, and sometimes, figuring out how to beat those ghosts that you’re dealing with, you need a little extra help,” Brewer said.

Last in, first out

Nebraska Gov. Jim Pillen identified the specialized diversion program as one of many “last in, first out” laws his budget proposal targeted for cuts or delayed implementation in January.

The recommendations temporarily ensnared or ended programs, including a prescription drug donation program costing about $500,000 annually, a step which was later reversed. The moves were part of Pillen’s answer to a then-projected$432 million state budget deficit through June 30, 2027.

The total budget hole lawmakers ultimately filled was much larger. In the case of the veterans justice program, Pillen’s recommendations argued the state court system could support veterans without additional taxpayer dollars.

“The Supreme Court is able to develop a process independently to address critical veteran justice needs,” Pillen’s budget recommendations said in mid-January.

Because the veterans justice program didn’t start until July 2025, lawmakers would have needed to find the $9.4 million for this budget year.

The Appropriations Committee accepted Pillen’s recommendation, and the full Legislature accepted the change with little opposition in the first year after legislative term limits sent home Brewer, Wayne and another lead supporter, former State Sen. Lou Ann Linehan of the Elkhorn area.

An effect of term limits

The trio joined a large class of lawmakers in 2017 and were among the most influential senators in recent years. Linehan chaired the Revenue Committee, and Brewer chaired the Government, Military and Veterans Affairs Committee.

Brewer, a 36-year military veteran with two Purple Hearts, served six combat tours in Afghanistan and two in Kyrgyzstan. He has since led nine volunteer missions to Ukraine after Russia invaded the country in February 2022 and plans to return next month.

The decorated veteran said he thought the decision would have been harder and that it would have been different had his class of “natural supporters” still been there. He said he would have “obviously fought it tooth and nail.”

© iStock - flySnow

But Brewer also expected other military veterans in the Legislature to step up.

“Maybe they didn’t want me barking at them, so they didn’t bother to let me know what was going on with it, but Justin [Wayne] notified me afterwards, and that’s the first I knew about it,” Brewer said.

Wayne said that while $5 million a year is big to everyday Nebraskans, it isn’t for the state budget or for those who have served the country. He said every dollar invested in problem-solving courts today, including those specific to veterans, yields a return of $8 to $10.

“The government put them in an area that caused it, so we as a government should take care of it,” Wayne said. “It’s unfortunate that Nebraska continues to fall behind in that.”

Brewer said Wayne came to him with the idea for the diversion program in the 2024 session, after bill introductions in their final session, but the two worked together with Linehan and other legislative leaders to find an unusual and speedy path to making it law.

“We weren’t sure if we could get it pushed through or not, but everything clicked,” Brewer said.

Dungan said he has seen and defended veterans facing criminal charges connected to their service. He said he recently attended a Lancaster County Veterans Treatment Court graduation, which was “one of the more moving things I’ve ever seen.”

“I understand that budgets are tight right now, but, again, it comes down to prioritization,” Dungan said. “I think that we absolutely have to prioritize the health and the welfare of vets across this entire state.”

A ‘fair number’

State Sen. Christy Armendariz of Omaha, Appropriations Committee vice chair, was among those who led the committee’s push to accept Pillen’s recommendation for the veterans program. She had told the Examiner during the 2025 session that her budget focuses were infrastructure, public safety and taking care of those who cannot take care of themselves, such as children and older adults.

In one executive session of the budget-writing committee in late March, she told her colleagues she felt the court hadn’t provided the Legislature a “fair number” and had inflated the estimated cost of a veterans justice program.

Armendariz was among those who supported the passage of the program the previous year, as did all other members of the Appropriations Committee at the time. An April 2024 fiscal note estimated the same $4.7 million annual cost that the Appropriations Committee and Pillen wrestled with this spring.

Nebraska Supreme Court Chief Justice Jeffrey Funke and State Court Administrator Corey Steel told the Legislature’s Appropriations Committee that the court system could not proceed with implementing the new program without the new funding. The plan is to add specialized probation officers, for instance, to monitor eligible veterans.

“I think we’re statutorily obligated to do that work,” Funke told the committee in his first budget cycle leading the court system. “We just don’t have the funding to do it.”

Steel told the Examiner in May that the fiscal estimate included roughly $3 million for staffing, $1 million for treatment costs and $500,000 for related information technology programming needs.

If the program had no state funding, it would have needed to go into effect July 1. But Steel told the Examiner in May, “The implementation would be very watered down and not implemented at the expectation that LB 253 was passed.”

Worsening budget trends

In late May, lawmakers took the extra step of formally delaying the implementation of the diversion program in state law, through Legislative Bill 150.

The Appropriations Committee almost advanced the delay without a separate public hearing on the proposal, but State Sen. Machaela Cavanaugh of Omaha urged the Judiciary Committee to hold one, partly because neither Pillen nor lawmakers had proposed the delay in the budget or in a separate bill.

With less than 24 hours’ notice, and with the budget having already passed, the Judiciary Committee hosted a short hearing the morning of May 22. It lasted no longer than 15 minutes, said State Sen. Rob Clements of Elmwood, Appropriations Committee chair..

“I do not want the Legislature to start a new program without a reasonable plan and proper funding,” Clements testified. He had sponsored the amendment delaying the program’s start.

State Sen. Wendy DeBoer of Omaha, vice chair of the Judiciary Committee, asked Clements why pushing the program out to 2027, to a new budget cycle for a different set of lawmakers, would be the “magic date.”

“Will you fund it?” DeBoer asked.

“Well, that’s part of the budget discussion. There wasn’t room for it in this year’s budget, and we’ll see how revenues and budgets are in the future,” Clements responded.

Since then, the state’s budget situation has worsened, with lawmakers projected to face another nearly half-a-billion-dollar deficit heading into the 2026 session that ends in mid-April.

Pillen also tried to trim the court system’s budget in late May, attempting to veto $12 million that court leaders said could have shuttered some critical court services, including a separate Veterans Treatment Court in Sarpy County. The Legislature deemed the vetoes had not been properly submitted, prematurely ending the fight and preserving the funds.

‘We’re ready to go’

Clements told the Examiner in May that a “problem” with the veterans justice program was that any veteran would be able to “claim he needs the veterans justice treatment” in any district or county court. He said judges and staff were not trained for that, suggesting a regional hub model as a possible alternative.

“I think the body will be favorable to that, so there’s some time to adjust the program down to what’s workable,” Clements said in a phone call.

At Clements’ hearing on the delay, DeBoer said she might consider seeking funding for the veterans program in 2026. She confirmed Monday night that she is still considering doing so in what would be her and Clements’ final year.

Pillen told the Examiner in a post-session interview that his office continued to support veterans statewide, including recognizing those who served in Vietnam, Korea and World War II.

“I think that there’s way more to supporting our veterans than just talking about more money,” Pillen said June 3, a day after the 2025 session ended.

Funke, in a wide-ranging interview this month about the judicial branch, said the courts continue to work to design the new veterans justice diversion program, which would supplement the existing state Veterans Treatment Courts. Judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys and more support those intensive programs designed to reduce recidivism and allow reentry to society.

“Once they say, ‘Yep, go forward, here’s the funding,’ we’re ready to go,” Funke said last week of the Legislature.

‘They didn’t kill it’

A national panel of senior military and criminal justice leaders designed the model policy that Nebraska was the first to pass last year. Former U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, chair of the national Veterans Justice Commission of the Council on Criminal Justice and a former U.S. senator from Nebraska, led the charge with Brewer, Wayne and Linehan.

Minnesota had passed a similar law a few years before the creation of the approach Nebraska adopted last year.

Wayne noted that the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council, which shares model conservative bills nationwide, touted Wayne and Brewer as bipartisan “policy champions” after the 2024 law. Wayne criticized Pillen and other supporters for breaking their promise.

Part of the reason for the legislation, Hagel said last year, was because of the difficulties of some servicemembers in transitioning back to civilian life. More than 200,000 active-duty members make that switch each year, a number exacerbated by the country’s long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Retired Brig. Gen. David MacEwen, director of the national Veterans Justice Commission and a former Army adjutant general between 2013 and 2015, said in a statement this month that the Nebraska law honors the sacrifices of veterans.

He said the new diversion program would ensure that those “entangled” in the legal system aren’t “forgotten” in jails or prisons and are supported.

“We understand that putting new laws into practice is never as smooth or as fast as we’d like, but we’re heartened to see that Nebraska remains committed to implementing this important reform,” MacEwen said.

Linehan, while reaffirming the importance of the law she helped champion, said in July that she wasn’t in a position to “second guess” the Legislature’s work this year. However, she said she looked forward to the state’s nationally praised court programs for veterans becoming more robust.

“I have every confidence in the governor and the leaders in the Legislature,” Linehan said. “They didn’t kill it. I’m happy about that.”

Readjusting to civilian life

Linehan, a former chief of staff for Hagel, served in the U.S. State Department between 2009 and 2012, where she worked on the Iraq desk. She worked in Iraq at the Baghdad Provincial Reconstruction Team and, in the end, headed the consulate in Basra after the Army left.

When she returned, Linehan said she was able to adjust back to the U.S., but she noted she wasn’t a young servicemember who spent four or five years in the military, who returned confused as to why others couldn’t understand their situation. She said support for veterans means helping with long-term reintegration, not just when they get off the plane.

“Nobody can understand what it’s like to be deployed,” Linehan said. “So we need to make sure, when we ask people to sacrifice everything, including some their lives and many their health, and especially their mental health, we need to make sure we’re there to help them.”

‘I just hope that our veterans matter’

According to the Council on Criminal Justice, roughly one in three veterans report being arrested or booked into jail at least once. The suicide rate for veterans is approximately 1.5 times higher than the rate among the general population and higher still for veterans who have been incarcerated.

Among all U.S. adults in 2022, there were, on average, more than 131 suicides each day and nearly 18 veteran suicides per day, according to the data reported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Brewer said the state’s delay makes him worry about the veterans who need the support the most. He said some worry more about their own struggles than the criminal penalties they face.

Brewer said a key reason veterans consider taking their own lives is a loss of hope and feeling as if no one cares. He said that was one of the problems he, Wayne, Linehan and Hagel sought to address.

Dungan passed a bill this year to systematically review veteran and general population suicides in the state and analyze ways to make a difference. Pillen supported those efforts. Lawmakers also explicitly banned discrimination on the basis of military or veteran status as part of LB 150.

Wayne said he wants lawmakers to care more about standing by veterans when they are in need or when they make a mistake, to not just make political speeches and appearances on Veterans Day or show up to banquets, but to help servicemembers and their families. He said the Legislature can always find money for things that matter.

“I just hope that our veterans matter enough to this Legislature to fund them.”