Study looks at what causes flash floods in the Appalachian mountains

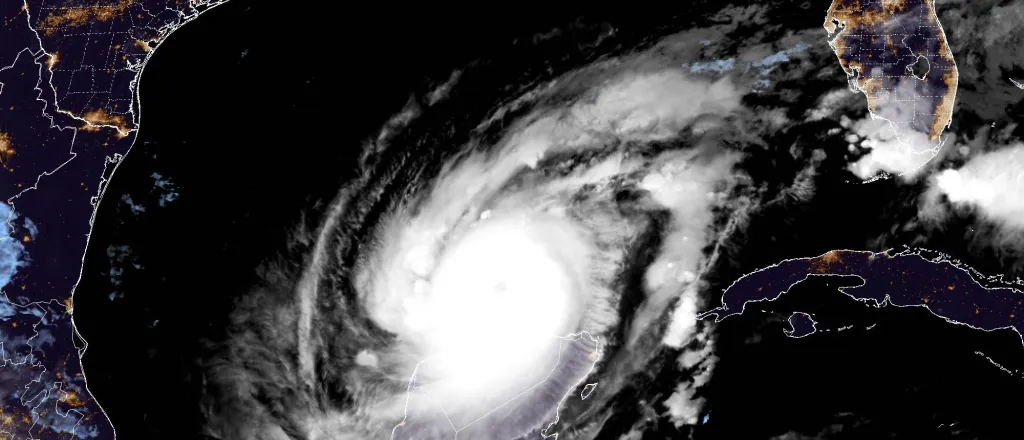

Hurricane Milton - October 10, 2024 - NOAA

Click play to listen to an abbreviated version of this article.

(Kentucky News Connection) In the wake of Hurricane Helene flooding areas of eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina, a new research study hopes to not only determine what causes flash flooding in the mountainous areas of Appalachia, but how to prepare residents for coming disasters.

In 2022, flash floods hit the hills of eastern Kentucky leaving in their wake, millions of dollars of devastation. A new research project at the University of Kentucky hopes to dive into what happened during that event and how planners can use that information to be better prepared in the future.

The four-year project will look at flash flooding in the small headwater streams in Appalachia. Part of a $77.8 million investment by the National Science Foundation into infrastructure improvements in the face of climate change, the study will bring together researchers from UK, the University of Louisville, Eastern Kentucky University, West Virginia University and Marshall University. Using sensors in streams and data from the Robison Forest, a teaching, research and extension forest in the Cumberland Plateau, researchers use the information they gather to identify specific issues related to flash floods.

© iStock - djperry

Kenton Sena, Ph.D., co-principal investigator and lecturer at UK, said sensors in the forest have been accumulating data for more than 50 years. The data will help them dig deeper into the temperatures, precipitation and weather conditions prior to flooding events which can lead to a better understanding of flooding scenarios. While national weather data can give researchers a daily precipitation amount, he said, the data from the Robinson Forest can give them hourly precipitation amounts.

“We can get a little bit more information out of the data like what kind of storm was this, was this a really intense thunderstorm where it rained cats and dogs for three hours and then stopped, or was this a more chill storm event that lasted for the whole day and was more gentle and less intense, because obviously the watershed will respond differently to those different scenarios with respect to flooding,” he said in an interview with the Daily Yonder.

Between July 25 and July 29, 2022, eastern Kentucky was hit with what the National Weather Service called the deadliest non-tropical weather event in the U.S. since the 1970s.

The rains started on July 25, but by the next morning, flash flood reports started coming in. Rains in excess of four inches an hour fell across 13 counties, inundating the area with upwards of 16 inches of rain.

By the evening of July 28 buildings, mobile homes and cars were swept down the valley as a wall of water left roads and bridges impassable and some residents trapped on hillsides. In the end, 45 people died and nearly 1,400 required rescuing. All 13 counties were declared federal disaster areas with nearly 9,000 homes damaged or destroyed and hundreds of families relocated to temporary shelters.

In 2023, a report from the Ohio River Valley Institute and Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center found that rebuilding the homes damaged in the 2022 flood would cost about $450 million, but relocating and replacing many of the homes to less flood-prone areas would raise the total to more than $950 million.

It’s not the first time the area had seen catastrophic flooding. According to a report by the Federal Reserve of Cleveland, the 13 county area has seen flooding 27 times.

The study may also help scientists better understand flooding in other areas, like the Hurricane Helene disaster in eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina. In September, tropical storms leftover from Hurricane Helene besieged the Great Smoky Mountains. Already saturated from days of storms prior to Helene’s arrival, some areas received nearly 30 inches of rain causing streams to overflow their banks and take out anything in their path.

The storm left at least 224 dead — 96 from North Carolina and 17 from Tennessee. North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper said Wednesday the storm caused more than $53 billion in damage. The state said the storm and its aftermath caused 1,400 landslides and damaged more than 160 water and sewer systems, 6,000 miles of roads, more than 1,000 bridges and culverts and an estimated 126,000 homes. In his request to the North Carolina legislature, Cooper asked for $3.9 billion to begin the process of rebuilding.

© iStock - Mijau

“Helene is the deadliest and most damaging storm ever to hit North Carolina,“ said Cooper. “This storm left a trail of destruction in our beautiful mountains that we will not soon forget, but I know the people of Western North Carolina are determined to build back better than ever.”

While the research can help with planning and prevention in the future, Sena said, the initial goal of the research is to save lives.

“We can look at what if we have a 2-inch rain event in three hours? We can look at what kinds of flood risk we’d be looking at,” he said. “And I think that helps us to build out the kind of predictive framework that we really need in order to move to a phase three which would be an on-the-ground meaningful warning (system) that will hopefully give folks time to evacuate.”

Additionally, he said, the researchers will be able to determine how best to communicate the threats to rural residents in a way that is meaningful to them.

“We’ll be working together… to better understand how the local community members would prefer to receive and distribute that kind of information,” he said. “Whatever we develop will hopefully be useful and ready to implement.”

Liz Carey wrote this article for The Daily Yonder.