Summer 2023 was the hottest on record, but don’t call it ‘the new normal’

Scott Denning, Colorado State University

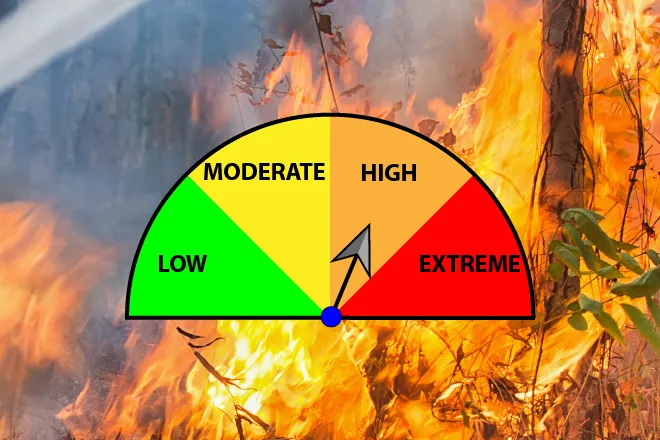

Summer 2023 was the hottest on record by a huge margin. Hundreds of millions of people suffered as heat waves cooked Europe, Japan, Texas and the Southwestern U.S. Phoenix hit 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius) for a record 54 days, including a 31-day streak in July. Large parts of Canada were on fire. Lahaina, Hawaii, burned to the ground.

As an atmospheric scientist, I get asked at least once a week if the wild weather we’ve been having is “caused” by climate change. This question reflects a misunderstanding of the difference between weather and climate.

Consider this analogy from the world of sports: Suppose a baseball player is having a great season, and his batting average is twice what it was last year. If he hits a ball out of the park on Tuesday, we don’t ask whether he got that hit because his batting average has risen. His average has gone up because of the hits, not the other way around. Perhaps the Tuesday homer resulted from a fat pitch, or the wind breaking just right, or because he was well rested that day. But if his batting average has doubled since last season, we might reasonably ask if he’s on steroids.

Unprecedented heat and downpours and drought and wildfires aren’t “caused by climate change” – they are climate change.

The rise in frequency and intensity of extreme events is by definition a change in the climate, just as an increase in the frequency of base hits causes a better’s average to rise.

And as in the baseball analogy, we should ask tough questions about the underlying cause. While El Niño is a contributor to 2023’s extreme heat, that warm event has only just begun. The steroids fueling extreme weather are the heat-trapping gases from burning coal, oil and gas for energy around the world.

Nothing ‘normal’ about it

A lot of commentary uses the framing of a “new normal,” as if our climate has undergone a step change to a new state. This is deeply misleading and downplays the danger. The unspoken implication of “new normal” is that the change is past and we can adjust to it as we did to the “old normal.”

Unfortunately, warming won’t stop this year or next. The changes will get worse until we stop putting more carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere than the planet can remove.

The excess carbon dioxide humans have put into the atmosphere raises the temperature – permanently, as far as human history is concerned. Carbon dioxide lingers in the atmosphere for a long time, so long that the carbon dioxide from a gallon of gasoline I burn today will still be warming the climate in thousands of years.

That warming increases evaporation from the planet’s surface, putting more moisture into the atmosphere to fall as rain and snow. Locally intense rainfall has more water vapor to work with in a warmer world, so big storms drop more rain, causing dangerous floods and mudslides like the ones we saw in Vermont, California, India and other places around the world this year.

By the same token, anybody who’s ever watered the lawn or a garden knows that in hot weather, plants and soils need more water. A hotter world also has more droughts and drying that can lead to wildfires.

So, what can we do about it?

Not every kind of bad weather is associated with burning carbon. There’s scant evidence that hailstorms or tornadoes or blizzards are on the increase, for example. But if summer 2023 shows us anything, it’s that the extremes that are caused by fossil fuels are uncomfortable at best and often dangerous.

Without drastic emission cuts, the direct cost of flooding has been projected to rise to more than US$14 trillion per year by the end of the century and sea-level rise to produce billions of refugees. By one estimate, unmitigated climate change could reduce per capita income by nearly a quarter by the end of the century globally and even more in the Global South if future adaptation is similar to what it’s been in the past. The potential social and political consequences of economic collapse on such a scale are incalculable.

Fortunately, it’s quite clear how to stop making the problem worse: Re-engineer the world economy so that it no longer runs on carbon combustion. This is a big ask, for sure, but there are affordable alternatives.

Clean energy is already cheaper than old-fashioned combustion in most of the world. Solar and wind power are now about half the price of coal- and gas-fired power. New methods for transmitting and storing power and balancing supply and demand to eliminate the need for fossil fuel electricity generation are coming online around the world.

In 2022, taxpayers spent about $7 trillion subsidizing oil and gas purchases and paying for damage they caused. All that money can go to better uses. For example, the International Energy Agency has estimated the world would need to spend about $4 trillion a year by 2030 on clean energy to cut global emissions to net zero by midcentury, considered necessary to keep global warming in check.

Just as the summer of 2023 was among the hottest in thousands of years, 2024 will likely be hotter still. El Niño is strengthening, and this weather phenomenon has a history of heating up the planet. We will probably look back at recent years as among the coolest of the 21st century.

This article was updated Sept. 15, 2023, with NOAA and NASA also confirming summer 2023 the hottest on record.![]()

Scott Denning, Professor of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.