There are plenty of moral reasons to be vaccinated – but that doesn’t mean it’s your ethical duty

Travis N. Rieder, Johns Hopkins University

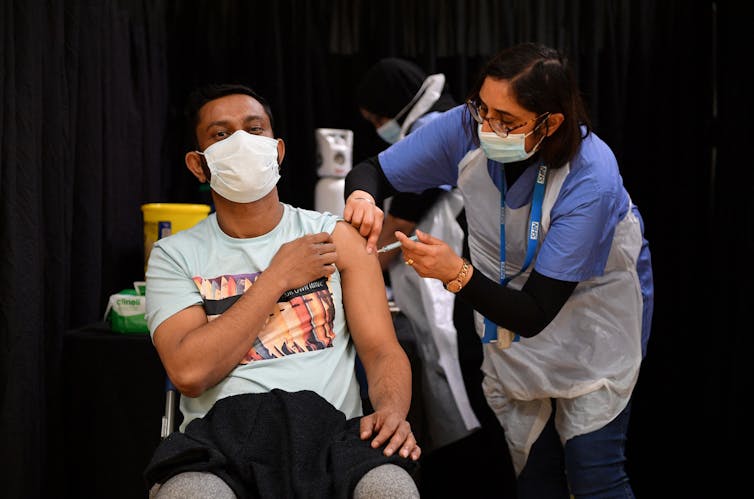

With the news that all U.S. adults are now eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the holy grail of infectious disease mitigation – herd immunity – feels tantalizingly close. If enough people take the vaccine, likely at least 70% of the population, disease prevalence will slowly decline and most of us will safely get back to normal. But if not enough people get vaccinated, COVID-19 could stick around indefinitely.

The urgency of reaching that milestone has led some to claim that individuals have a civic duty or moral obligation to get vaccinated.

As a moral philosopher who has written on the nature of obligation in other contexts, I want to explore how the seemingly straightforward ethics of vaccine choice is in fact rather complex.

The simple argument

The discussion of whether or not one should take the COVID-19 vaccine is often framed in terms of individual self-interest: The benefits outweigh the risk, so you should do it.

That’s not a moral argument.

Most people likely believe that others have wide latitude in determining how they care for their own health, so it can be permissible to engage in risky activities – such as motorcycling or base jumping – even when it’s not in one’s interest. Whether one should get vaccinated, however, is a moral issue because it affects others, and in a couple of ways.

First, effective vaccines are expected to decrease not only rates of infection but also rates of virus transmission. This means that getting the vaccine can protect others from you and contribute to the population reaching herd immunity.

Second, high disease prevalence allows for more genetic mutation of a virus, which is how new variants arise. If enough people aren’t vaccinated quickly, new variants may develop that are more infectious, are more dangerous or evade current vaccines.

The straightforward ethical argument, then, says: Getting vaccinated isn’t just about you. Yes, you have the right to take risks with your own safety. But as the British philosopher John Stuart Mill argued in 1859, your freedom is limited by the harm it could do to others. In other words, you do not have the right to risk other people’s health, and so you are obligated to do your part to reduce infection and transmission rates.

It’s a plausible argument. But the case is rather more complicated.

Individual action, collective good

The first problem with the argument above is that it moves from the claim that “My freedom is limited by the harm it would cause others” to the much more contentious claim that “My freedom is limited by very small contributions my action might make to large, collective harms.”

Refusing to be vaccinated does not violate Mill’s harm principle, as it does not directly threaten some particular other with significant harm. Rather, it contributes a very small amount to a large, collective harm.

Since no individual vaccination achieves herd immunity or eliminates genetic mutation, it is natural to wonder: Could we really have a duty to make such a very small contribution to the collective good?

A version of this problem has been well explored in the climate ethics literature, since individual actions are also inadequate to address the threat of climate change. In that context, a well-known paper argues that the answer is “no”: There is simply no duty to act if your action won’t make a meaningful difference to the outcome.

Others, however, have explored a variety of ways to rescue the idea that individuals must not contribute to collective harms.

One strategy is to argue that small individual actions may actually make a difference to large collective effects, even if it’s difficult to see.

For instance: Although it appears that an individual getting vaccinated doesn’t make a significant difference to the outcome, perhaps that is just the result of uncareful moral mathematics. One’s chance of saving a life by reducing infection or transmission is very small, but saving a life is very valuable. The expected value of the outcome, then, is still high enough to justify taking it to be a moral requirement.

Another strategy concedes that individual actions don’t make a meaningful difference to large, structural problems, but this doesn’t mean morality must be silent with regard to those actions. Considerations of fairness, virtue and integrity all might recommend taking individual action toward a collective goal – even if that action did not by itself make a difference.

In addition, these and other considerations can provide reasons to act, even if they don’t imply an obligation to act.

The contours of obligation

There is yet another challenge in justifying an obligation to get vaccinated, which has to do with the very nature of obligations.

Obligations are requirements on actions, and, as such, those actions often seem demandable by members of the moral community. If a person is obligated to donate to charity, then other members of the community have the moral standing to demand a percentage of their income. That money is owed to others.

The relevant question here, then, is: Are there moral grounds to demand another person get vaccinated?

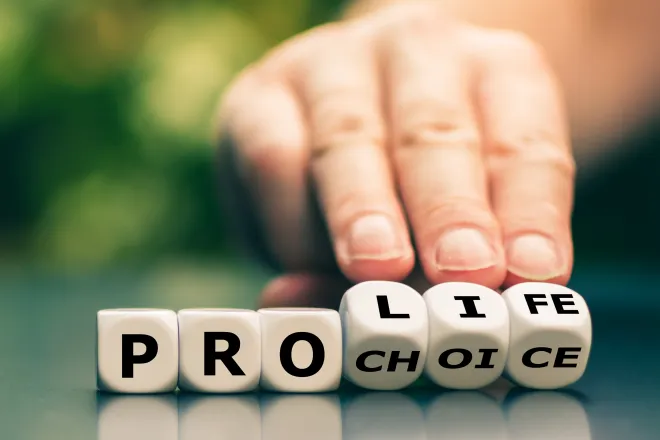

Philosopher Margaret Little has argued that very intimate actions, such as sex and gestation – the continuation of a pregnancy – are not demandable. In my own work, I’ve suggested that this is also true for deciding how to form a family – for example, adopting a child versus procreating. The intimacy of the actions, I argue, make it the case that no one is entitled to them. Someone can ask you for sex, and there are good reasons to adopt rather than procreate; but no one in the community has the moral standing to demand that you do either. These sorts of examples suggest that particularly intimate actions are not the appropriate targets of obligation.

Is getting vaccinated intimate? While it may not appear so at first blush, it involves having a substance injected into your body, which is a form of bodily intimacy. It requires allowing another to puncture the barrier between your body and the world. In fact, most medical procedures are the sort of thing that it seems inappropriate to demand of someone, as individuals have unilateral moral authority over what happens to their bodies.

The argument presented here objects to intimate duties because they seem too invasive. However, even if members of the moral community don’t have the standing to demand that others vaccinate, they are not required to stay silent; they may ask, request or entreat, based on very good reasons. And of course, no one is required to interact with those who decline.

The upshot

I am certainly not trying to convince anyone that it’s OK not to get vaccinated. Indeed, the arguments throughout indicate, I think, that there is overwhelming reason to get vaccinated. But reasons – even when overwhelming – don’t constitute a duty, and they don’t make an action demandable.

Acting as though the moral case is straightforward can be alienating to those who disagree. And minimizing the moral stakes when we ask others to have a substance injected into their body can be disrespectful. A much better way, I think, is to engage others rather than demand from them, even if the force of reason ends up clearly on one side.

[Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion.]![]()

Travis N. Rieder, Director of the Master of Bioethics degree program at the Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.