Western river compacts were innovative in the 1920s but couldn’t foresee today’s water challenges

Patricia J. Rettig, Colorado State University

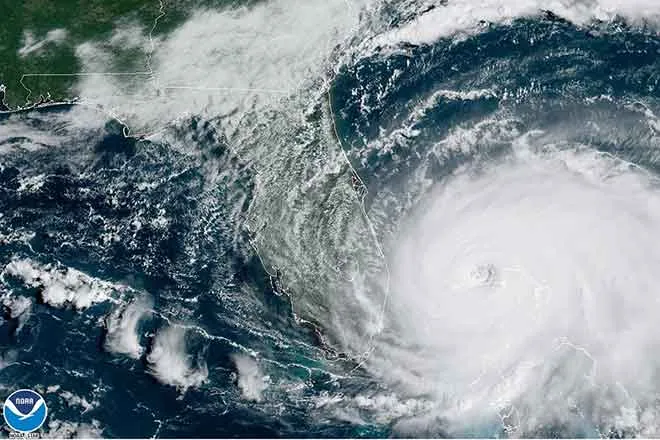

The Western U.S. is in a water crisis, from California to Nebraska. An ongoing drought is predicted to last at least through July 2022. Recent research suggests that these conditions may be better labeled aridification – meaning that warming and drying are long-term trends.

On the Colorado River, the country’s two largest reservoirs – Lake Powell and Lake Mead – are at their lowest levels in 50 years. This could threaten water supplies for Western states and electricity generation from the massive hydropower turbines embedded in the lakes’ dams. In August 2021 the federal government issued a first-ever water shortage declaration for the Colorado, forcing supply cuts in several states.

The seven Colorado River Basin states – Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming – signed a water sharing agreement, the Colorado River Compact, in 1922. Some observers are now calling for renegotiating the compact to correct errors and oversights. Nebraska and Colorado are also arguing over water from the South Platte River, which they share under a separate agreement signed in 1923.

My work as head archivist for Colorado State University’s Water Resources Archive gives me a unique perspective on these conflicts. Our collection includes the papers of Delph Carpenter, a lawyer who developed the concept of interstate river compacts and negotiated both the Colorado and South Platte agreements.

Carpenter’s drafts, letters, research and reports show that he believed compacts would reduce litigation, preserve state autonomy and promote the common good. Indeed, many states use them now. Viewing Carpenter’s documents with hindsight, we can see that interstate river compacts were an innovative solution 100 years ago – but were written for a West far different from today.

Water for development

In the early 1900s, there was plenty of water to go around. But there weren’t enough dams, canals or pipelines to store, move or make use of it. Devastating floods in California and Arizona spurred plans for building dams to hold back high river flows.

With the Reclamation Act of 1902, Congress directed the Interior Department to develop infrastructure in the West to supply water for irrigation. As the Reclamation Service, which later became the powerful Bureau of Reclamation, moved forward, it began planning for dams that could also generate hydropower. Low-cost electricity and irrigation water would become important drivers of development in the West.

Carpenter worried that downstream states, building dams for their own needs, would demand water from upstream states. He was especially attuned to this issue as a native of mountainous Colorado, the source of four major rivers – the Platte, the Arkansas, the Rio Grande and the Colorado. Carpenter wanted to see upper basin states “adequately protected before the construction of the structures upon the lower river.”

Carpenter also knew about interstate water conflicts. In 1916, a group of Nebraska irrigators sued farmers in Colorado for drying up the South Platte River at the state line. Carpenter was already lead counsel for Colorado in Wyoming v. Colorado, a case involving the Laramie River that began in 1911 and would not be resolved until 1922.

Carpenter viewed such legal battles as wastes of time and money. But when he proposed negotiating interstate river compacts, he was met with “skepticism, indifference, failure of comprehension or open ridicule,” he recollected in a 1934 essay.

Eventually Carpenter persuaded his Colorado clients to resolve their litigation with Nebraska by negotiating a compact to share water from the South Platte. It took seven years of data collection and discussion, but Carpenter believed the agreement would ensure “permanent peace with our neighboring state.”

Or maybe not. Today Nebraska officials want to revive an unfinished canal to pull water from the South Platte in Colorado, citing concerns about Colorado’s numerous planned upstream water projects. With Colorado officials pledging to aggressively defend their state’s water rights, the states could be headed to court.

Portioning out the Colorado

West of the Continental Divide, the Colorado River flows more than 1,400 miles southwest to the Gulf of California in Mexico. Once, its delta was a lush network of lagoons; now the river peters out in the desert because states take so much water out of it upstream.

When settlers developed the West, their prevailing attitude was that water reaching the sea was wasted, so people aimed to use it all. California had a bigger population than the other six Colorado River Basin states combined, and Carpenter worried that California’s river use could hinder Colorado under the prior appropriation doctrine, which dictates that the first person to use water acquires a right to use it in the future. With the U.S. Reclamation Service studying the Colorado to find good dam sites, Carpenter also feared that the federal government would take control of river development.

Carpenter studied international treaties as models for river compacts. He knew that U.S. states had a right under Article 1, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution to make agreements with each other. And he believed that solving water conflicts between states required “statesmanship of the highest order.”

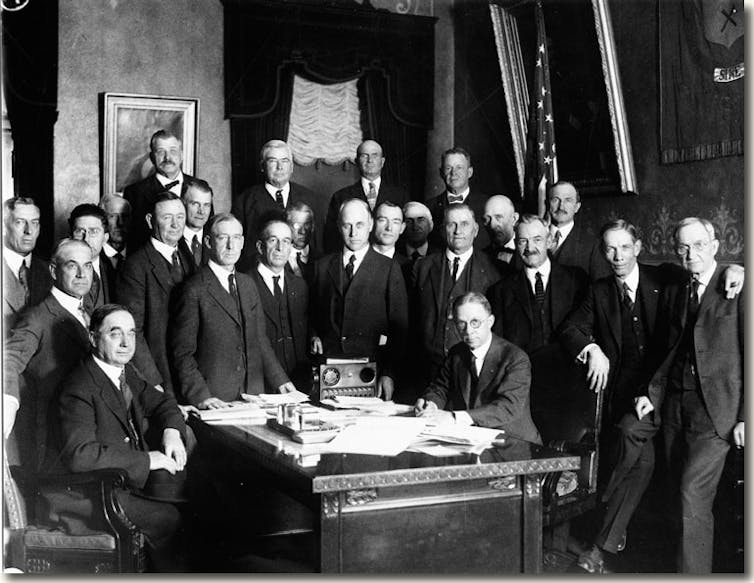

In 1920, officials agreed to try his approach. After the states and the federal government adopted legislation to authorize the process, representatives began meeting as the Colorado River Commission in January 1922, with then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover as chair. Meeting minutes show that negotiations nearly collapsed several times, but the end goal of rapid river development held them together.

The commissioners reached agreement in 11 months, adopting a final version of the compact in November 1922. It allocated fixed amounts of water – measured in absolute acre-feet, not percentages of the river’s flow – to the upper and lower basins. With water levels in the river declining, this approach has proved to be a major challenge today.

At their meetings, the commissioners discussed both the variability of the river’s flow and their lack of sufficient data for long-term planning. Yet in the final compact they allowed for dividing up surplus water starting in 1963. We know now that they used optimistic flow numbers measured during a particularly wet period.

A hotter, more crowded West

Today the West faces conditions that Carpenter and his peers did not anticipate. In 1922, Hoover imagined that the basin’s population, which totaled about 457,000 in 1915, might quadruple in the future. Today, the Colorado River supplies some 40 million people – more than 20 times Hoover’s projection.

The commissioners also didn’t anticipate climate change, which is making the west hotter and drier and shrinking the river’s volume. Some water experts say a new agreement is needed that recognizes an era of shortage. Others say renegotiation is politically impossible. The states signed a drought contingency plan in 2019, but it runs through only 2026.

Testifying before Congress in 1926 about the Colorado River Compact, Hoover stated, “If we can provide for equity for the next 40 to 75 years we can trust to the generation after the next to be as intelligent as we are today.” In the face of extreme Western water challenges, it is now up to Westerners to meet – or exceed – that expectation.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Patricia J. Rettig, Head Archivist, Water Resources Archive, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.