Curious Kids: Why is astronomy a science but astrology is not?

Talia Dan-Cohen, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis and Carl Craver, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why is astronomy a science, but not astrology? – Katelyn, age 11, Arlington, Texas

Are you sure astrology isn’t a science?

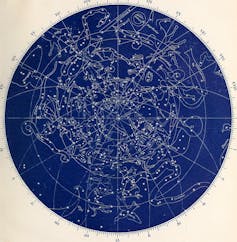

Both astrology and astronomy are in the business of making predictions. The theories of astrology claim that the positions of the planets and the stars influence who you are and what happens to you: your job, your personality and your romantic partner. Astrologers make these predictions based on the positions of the planets at the time of your birth.

Astronomy, in contrast, makes predictions about such phenomena as the movements of planets and the expansion of galaxies. Astronomers explain their predictions with such properties as masses, distances and gravitational forces.

As a philosopher and an anthropologist who study what science means to society, we think it is important to separate the question of whether something is a science from the question of whether it is true or false.

Astrology makes scientific claims

Science, in essence, involves making and testing factual claims about the world. Factual claims are true or false descriptions of the world (Joe is 1 meter tall) as opposed to descriptions of how we define things (1 meter is 1,000 milimeters). In this sense, astrologers, like astronomers, make factual claims about the world. To us, that makes astrology sound a lot like a set of scientific beliefs.

For a very long time, until the 17th or 18th century, astronomy and astrology were practiced side by side. After all, knowing where the planets were relative to the stars was necessary to make accurate predictions about how their locations influenced human affairs. That’s why astronomers and astrologers populated medical schools and governments, advising people on what the heavens signaled was to come on Earth.

Even famed astronomers Galileo and Kepler practiced astrology. Any rule that says they are scientists only if they make one set of factual claims but not when they make another set of factual claims divides these thinkers into two halves that aren’t meant to be contradictory. In both cases, they wanted to know how things worked so they could predict how things would go in the future.

Being false vs. being unscientific

But here’s the rub: When researchers test the predictions astrology makes about people’s lives, those predictions turn out to be no better than guesswork.

There is currently no broadly accepted evidence that galactic forces are capable of influencing the choices people make. The truck parked on the street exerts more gravitational pull on you than Mars does, and the radio waves from your local station far outpower those from Jupiter, for instance.

There is an important difference between being false and being unscientific. Currently, astrological theories are false precisely because they make scientific claims about the world, and those claims turn out to be wrong. Although the predictions astrology makes are false, they are nonetheless a matter of science. That’s how we know they are wrong, after all.

Some people believe they find support for astrological predictions in their own personal experience. They read their horoscope and it seems just right: They did “meet someone interesting” or “benefit from listening to a close friend’s advice.” But the predictions are vague enough that they would often be true even if astrology were utterly bogus. That’s why it can be difficult to figure out how to assess an astrologer’s predictions with precision.

Theories of astronomy, on the other hand, have evolved over the years with advances in technology. They are routinely corrected in response to increasingly precise measurements. For example, Einstein’s theory of general relativity got a boost over Newton’s because it predicted the precise migration of Mercury’s closest point to the Sun year after year. If astrology had the same ability to make correct predictions with such precision, it might still be a major focus of scientific attention.

Why is astrology still popular?

But then why do so many people find astrology so useful if its predictions are not well founded? Why are astrological signs and horoscopes so popular?

It seems that looking to the sky to make some sense of what’s going on right now and what’s going to happen in the future has appealed to a lot of different people at different times in history all over the world.

When it comes to what’s commonly known as Western astrology, many people find their astrological sign to be a source of meaning in their lives. In fact, nearly 30% of Americans believe in astrology. It’s one of many tools we have for telling stories about ourselves to make sense of who we are, why we are that way and why experiences that otherwise would feel meaningless and confusing seem to happen to us all the time. In this sense, astrology’s success might be less about prediction and more about what it offers in terms of meaning and interpretation.

Among other things, astrology can be a useful prompt for self-reflection. It asks us whether we have traits typical of our astrological sign, and whether those we love have traits the theory suggests they ought to have. Thinking about our traits and relationships with the people around us is generally a good tool for understanding who we are, what we want to be and the meaning of our lives. Perhaps astrology is helpful in this way, independently of whether those traits are fixed by the stars.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Talia Dan-Cohen, Associate Professor of Sociocultural Anthropology, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis and Carl Craver, Professor of Philosophy and Philosophy-Neuroscience-Psychology, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.