Drought, warmer winters make Colorado forests 'beetle buffet'

Click play to listen to this article.

Warmer winters and prolonged drought have turned Colorado forests into a budworm and beetle buffet, according to a new report from Colorado State University, and the thousands of acres of dead and dying trees left in their wake pose wildfire risks.

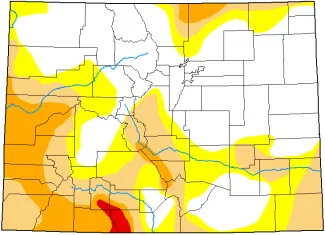

Dan West, entomologist for the Colorado State Forest Service, said four of the last five years have seen below-average precipitation, which is a problem because trees need water to produce resin, which they use to fight off insects.

"When we have significantly below or below-average precipitation, you couple that with warmer than average temperatures, it's really hard to be a tree in Colorado," West explained. "A lot of these bark beetles are just taking advantage of that."

©

Between 2023 and 2024, western spruce budworms increased their feasting grounds to 217,000 acres, up 15,000 acres from the previous year. The mountain pine beetle population continues to grow along the Front Range, in Gunnison County and in the southwest corner of the state. Bark beetles, the state's deadliest because they kill entire trees, have devoured 27,000 acres in places such as Rocky Mountain National Park and the San Juan and San Isabel national forests.

Warmer winters due to the burning of fossil fuels have taken away a key tree defense: deep freezes. West noted Colorado has not seen below-average winter temperatures in more than three decades.

"Maybe in my parents' generation or grandparents' generation, we used to calculate in overwinter mortality of bark beetles," West pointed out. "We pretty much don't do that anymore. The temperatures really never reach that overwintering cold temperature that can cause bark beetle mortality."

West added trees and insects naturally coexist in ecosystems and bark beetles act as sanitizers of the forest by recycling nutrients but with entire forests weakened, trees become low-hanging fruit.

"As these outbreaks continue over a number of years, we've got a lot of standing dead trees," West observed. "A cigarette, a campfire, a lightning strike -- whatever the spark may be -- that then has a lot of fuel to be able to burn through."