Flood and wildfire risks: Translating risk ratings into future costs can help homebuyers and renters grasp the odds – and act on them

Melanie Gall, Arizona State University; Christopher Emrich, University of Central Florida, and Marie Aquilino, Arizona State University

If you look at homes on real estate websites today, you’ll likely see risk ratings for flooding, hurricanes and even wildfires.

In theory, summarizing risk information like this should help homebuyers and renters make more informed housing choices. But surveys show it isn’t working that way, at least not yet. Housing developments and home sales are still expanding in flood- and wildfire-prone areas.

The problem isn’t necessarily that consumers are ignoring the numbers. In our view, as experts in hazards geography, it’s that the way risk information is being presented ignores long-established lessons from behavioral science.

These ratings tend to appear as a single number for each hazard and lack an intuitive interpretation. What does it mean to have a heat risk of 84 (“extreme”) with 52 hot days in 2050, or a flood risk of 10 (“extreme”)?

We believe that current and future hazard and climate risks can more effectively be translated as costs, savings and trade-offs.

Making risk personal

Studies show that people rely on personal experience as the dominant driver when considering risk. In the absence of having personally experienced a flood or wildfire damage, they need actionable and understandable information.

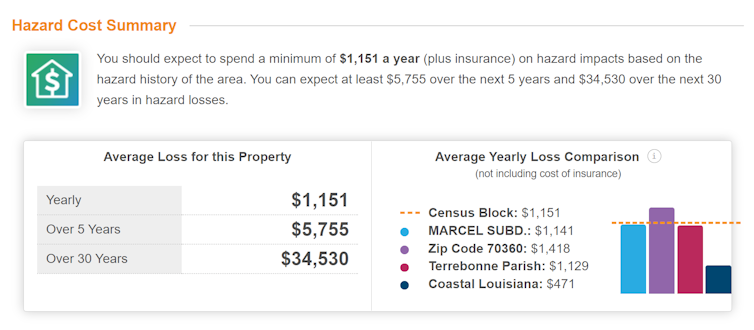

We belong to a group of more than 20 interdisciplinary researchers at universities in Arizona, Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina who are trying to improve risk rating information. We’re currently testing an online tool for the Gulf Coast that provides residents with actionable resilience information. It is an early model of what residential risk reporting could look like.

Rather than just presenting a score, the tool offers information on the costs annually and over time that one can expect from each hazard, such as flooding or wind damage, and how the home’s census block compares with the local area, county and state. To capture the effects of sea-level rise, for example, we model the number of years it will take for a home to go from outside a high flood risk area to being inside.

Homebuyers’ psychological hurdles

The development of real estate-focused climate and hazard risk metrics, such as those offered by First Street Foundation and ClimateCheck, is a step in the right direction, going beyond government risk maps that provide risk data by county. The next step is to ground those numbers in behavioral science research.

People do not ignore risk ratings per se, but the point at which information motivates people to take protective actions varies.

The motivation hurdle is lower for people with past experience, those who are aware of the risks and receptive to this kind of information, and those who have the financial resources to choose safer communities.

For others, the hurdle can be much higher. They might struggle with common decision biases, such as oversimplifying the severity of the risk, which leads to either an overestimation or underestimation of the threat depending on the type of hazard, focusing on today rather than the future, or simply assuming nothing bad is going to happen. They might just follow what others do – which research finds is what most of us do when deciding on a home.

Many people also have unrealistic beliefs that insurance and government payouts after disasters will fully compensate them for their losses, and a false sense of security that building codes and permitting mean homes are built to withstand any natural hazard.

The combination of these decision biases causes residents to underestimate the risk and impacts from disasters and climate change. Most people then underprepare and don’t consider these risks in their housing choices.

Risk ratings could help overcome those biases by expressing risk information in relatable terms such as the number of assistance requests made to the Federal Emergency Management Agency after disasters, the rejection rate and the average FEMA funds received per applicant in the area.

Next step: Pull it all together in one location

Ideally, homebuyers and renters would have a one-stop shop for all of this risk information about a property. To be prepared for climate change, risk must become a factor in housing choices similar to square footage and number of bedrooms.

Currently, risk data is scattered. For example, people can learn about insurance costs by checking flood insurance rate maps, which outline the areas with a 1% or greater annual chance of flooding. Or they can ask an insurance agent to generate a Comprehensive Loss Underwriting Exchange report, which lists all flood insurance claims made on a property in the past five to seven years. A handful of states such as California require sellers to disclose the risk of natural hazards to the property.

In our view, the continuing influx of residents into high-risk areas, along with skyrocketing disaster losses, presents an urgent need to give prospective renters and buyers better information about the risks properties face.![]()

Melanie Gall, Clinical Professor and Co-Director, Center for Emergency Management and Homeland Security, Watts College, Arizona State University; Christopher Emrich, Associate Professor of Public Administration, University of Central Florida, and Marie Aquilino, Senior Research Analyst in Emergency Management, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.