Hurricane Henri expected to bring dangerous storm surge to Northeast states – but what is storm surge, anyway?

Anthony C. Didlake Jr., Penn State

Forecasters warned about the potential for dangerous storm surge as Henri strengthened into a hurricane on a path expected to take its eye over or near New York’s Long Island and into New England on Aug. 22, 2021. The storm was expected to reach the coast at full moon, when high tides are higher than normal already. Here’s how Anthony Didlake Jr., a meteorologist at Penn State, recently explained how storm surge forms and why it’s so dangerous.

What is storm surge?

Of all the hazards that hurricanes bring, storm surge is the greatest threat to life and property along the coast. It can sweep homes off their foundations, flood riverside communities miles inland, and break up dunes and levees that normally protect coastal areas against storms.

As a hurricane reaches the coast, it pushes a huge volume of ocean water ashore. This is what we call storm surge.

This surge appears as a gradual rise in the water level as the storm approaches. Depending on the size and track of the hurricane, storm surge flooding can last for several hours. It then recedes after the storm passes.

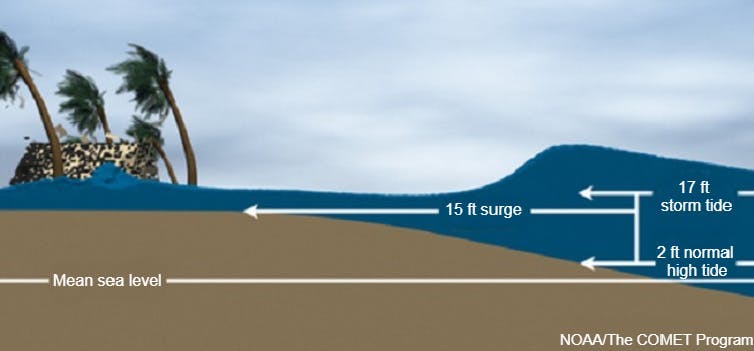

Water level heights during a hurricane can reach 20 feet or more above normal sea level. With powerful waves on top of it, a hurricane’s storm surge can cause catastrophic damage.

What determines how high storm surge gets?

Storm surge begins over the open ocean. The strong winds of a hurricane push the ocean waters around and cause water to pile up under the storm. The low air pressure of the storm also plays a small role in lifting the water level. The height and extent of this pile of water depend on the strength and size of the hurricane.

As this pile of water moves toward the coast, other factors can change its height and extent.

The depth of the sea floor is one factor.

If a coastal area has a sea floor that gently slopes away from the coastline, it’s more likely to see a higher storm surge than an area with a steeper drop-off. Gentle slopes along the Louisiana and Texas coasts have contributed to some devastating storm surges. Hurricane Katrina’s surge in 2005 broke levees and flooded New Orleans. Hurricane Ike’s 15- to 17-foot storm surge and waves swept hundreds of homes off Texas’ Bolivar Peninsula in 2008. Both were large, powerful storms that hit in vulnerable locations.

The shape of the coastline can also shape the surge. When storm surge enters a bay or river, the geography of the land can act as a funnel, sending the water even higher.

Other factors that shape storm surge

Ocean tides – caused by the gravity of the moon and sun – can also strengthen or weaken the impact of storm surge. So, it’s important to know the timing of the local tides compared to the hurricane landfall.

At high tide, the water is already at an elevated height. If landfall happens at high tide, the storm surge will cause even higher water levels and bring more water further inland. The Carolinas saw those effects when Hurricane Isaias hit at close to high tide on Aug. 3, 2020. Isaias brought a storm surge of about 4 feet at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, but the water level was more than 10 feet above normal.

Sea level rise is another growing concern that influences storm surge.

As water warms, it expands, and that has slowly raised sea level over the past century as global temperatures have risen. Freshwater from melting of ice sheets and glaciers also adds to sea level rise. Together, they elevate the background ocean height. When a hurricane arrives, the higher ocean means storm surge can bring water further inland, to a more dangerous and widespread effect.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Anthony C. Didlake Jr., Assistant Professor of Meteorology, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.