At last, COVID-19 shots for little kids

Amanda Mascarelli, The Conversation

For many parents of kids under age 5, a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine could not come soon enough. A full year and a half after shots first became available for adults, their wait is nearly over.

On June 17, 2022, the Food and Drug Administration authorized both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 shots for the nearly 20 million U.S. children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years. The widely anticipated decision follows a unanimous recommendation in favor of the shots by the FDA’s independent advisory panel.

The remaining critical step is for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to sign off on the shots, which is expected to take place within days.

The following collection of articles from The Conversation’s archives traces the winding path of the development of COVID-19 vaccines for the youngest children, from the early days of clinical trials to the practical challenges of how to help kids overcome their fears and anxieties over getting a shot.

1. ‘Kids aren’t just littler adults’

As the delta variant raged across the country in the summer of 2021, parents of kids under age 12 were anxiously awaiting the availability of a safe and effective COVID-19 shot for that age group. The FDA’s authorization for ages 5 to 11 finally came in October 2021. But that still left the preschool and younger kids waiting for their own version of the vaccine.

In July 2021, Judy Martin, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh Health Sciences, helped pull back the curtain for our readers on the often mysterious and slow-going clinical research studies that must take place before vaccines are authorized for children. Martin explained how the developing brains, bodies and immune systems of infants and young children differ from those of older children, and how that is taken into account during vaccine development, clinical trials and safety assessment.

2. So you get a shot, then what?

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned a lot of once-obscure biology terms such as mRNA, spike proteins and “waning antibodies” into household words. Yet for all the talk of vaccines and immunology, few people have a deep understanding of just what exactly happens once a vaccine is injected into the body.

One curious 12-year-old posed that very question to The Conversation: “How does a COVID-19 vaccine work in the body?” So we asked Glenn J. Rapsinski, a pediatric infectious diseases expert at the University of Pittsburgh Health Sciences, to tackle that question for our Curious Kids series – at a level that young kids and adults alike can appreciate.

When the body encounters the molecules in a COVID-19 vaccine – which mimics the SARS-CoV-2 virus – it activates an intricate and coordinated set of cells and processes. It’s a lot like an elaborate construction zone. Some of these cells alert the body to the invader and recruit helpers, flagging the invader with signals akin to “flashing neon yellow signs.”

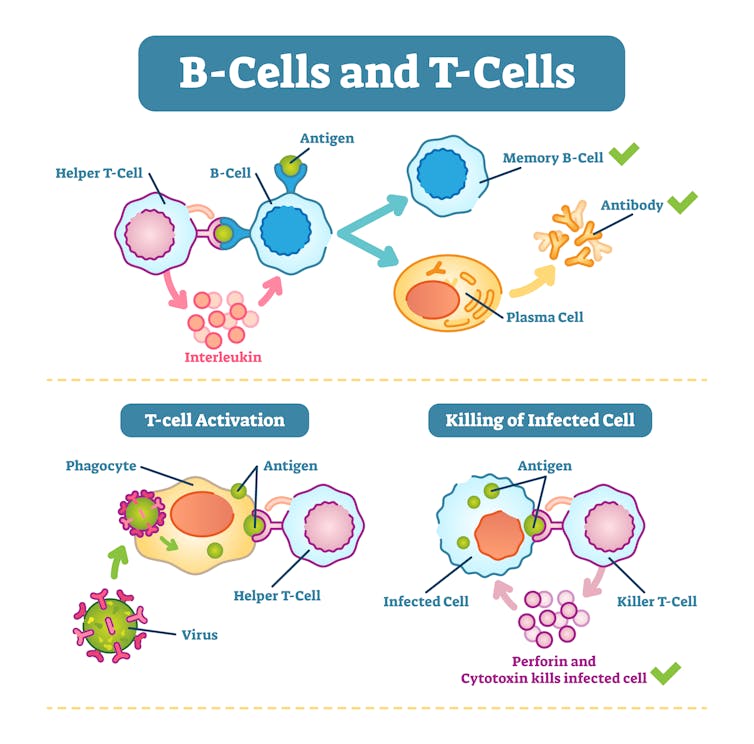

“As all of these important processes are happening inside your body, you might see some physical signs that there’s a struggle going on underneath the skin,” Rapsinski explained. “If your arm gets sore after you get the shot, it’s because immune cells like the dendritic cells, T-cells and B-cells are racing to the arm to inspect the threat.”

3. Training the immune system

As clinical trials of COVID-19 shots for children under age 5 crawled along in early 2022, the omicron variant gained a firm foothold in the U.S. While serious cases of COVID-19 remain relatively rare in children, hospitalizations in kids under 5 increased dramatically due to the heightened transmissibility of omicron, highlighting the urgent need for a safe vaccine in that age group.

Debbie-Ann Shirley, a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Virginia, wrote in March 2022 about the painstaking process of performing clinical trials sequentially for each descending age group.

“Several factors determine how our bodies respond to vaccines, and one of these variables is age,” Shirley explained. “Testing by age groups helps to account for these differences in how the maturing immune system responds to different types of vaccines. It is common for childhood vaccines to be given in series to help train the young immune response to make better and stronger antibody responses with each subsequent dose.”

4. The inevitable booster shot question

In the fall of 2021, a mounting body of data from adults and adolescents found that immunity from COVID-19 vaccines and infections was waning over time, suggesting that booster shots would be needed – especially in the face of omicron. The same trends proved true for the 5 to 11 age group, though vaccination continued to provide strong protection against severe COVID-19 that leads to hospitalization. So in May 2022, the CDC recommended a booster dose for 5- to 11-year-olds.

COVID-19 shots for infants and preschoolers are expected to follow a similar trajectory; Pfizer’s COVID-19 shots for kids under age 5 are intended to be a three-dose series. Moderna’s testing of the third dose is still underway. In May 2022, Shirley provided a snapshot of those studies and explained how researchers were determining that the third shots were safe and effective.

5. Helping kids overcome fear of shots

While the wait for COVID-19 vaccines for young children has undoubtedly been excruciating for some parents, so might be their conversations with children who have serious anxiety over getting a shot. Lynn Gardner, an associate professor of pediatrics at Morehouse School of Medicine and a primary care pediatrician, has helped thousands of parents and their children cope with the very real fears that can surface in the doctor’s office.

Gardner wrote about what she calls the “Three P’s” – preparation, proximity and praise – that parents and caregivers can use to lessen their children’s anxiety around shots and help them have a more positive experience.

“It is essential that you ask your child how they are feeling about receiving a shot,” she explained. “Giving them the opportunity to express their feelings can decrease the amount of stress and anxiety they feel about it. Validate their feelings by telling them you know needles can be a bit scary, but then reassure them that they can handle it. Explain why they’re receiving vaccines and emphasize it is for their overall good.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.![]()

Amanda Mascarelli, Senior Health and Medicine Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.