The 'yield curve' is one of the most accurate predictors of a future recession – and it's flashing warning signs

© iStock - Mamphotography

Julius Probst, Lund University

More than ten years on from the global financial crisis and economies around the world are still struggling to fully recover. The latest data is not promising. International institutions such as the OECD, IMF and World Bank have all recently downgraded their growth forecasts for the current and upcoming year.

Compared to just a year ago, all major economies are now expected to grow significantly slower than what was previously expected. For the US, the phasing out of Donald Trump’s tax cuts will negatively affect the economy. And the global trade war is starting to weigh down on the global economy, with some major exporting countries like Germany and Japan being affected the most.

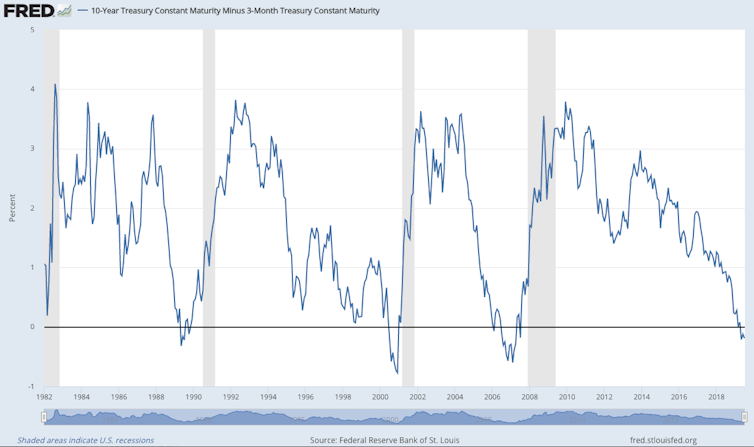

More importantly, one of the most accurate recession indicators, known as the yield curve, has recently been flashing warning signs. Every postwar recession in the US was preceded by an inversion of the yield curve, meaning that long-term interest rates had fallen below short-term interest rates, some 12 to 18 months before the outset of the economic downturn.

There are many different interest rates in the economy. In general, the interest rate must reflect the riskiness of the borrower and the type of investment that is carried out.

The time structure of the loan also matters. Governments issue debt with very different maturities – from short-term Treasury bills in the US that mature within one year or less to long-term bonds, which can have maturities of two years to 30 years. Some countries like France and Spain even have government bonds with a duration of 50 years.

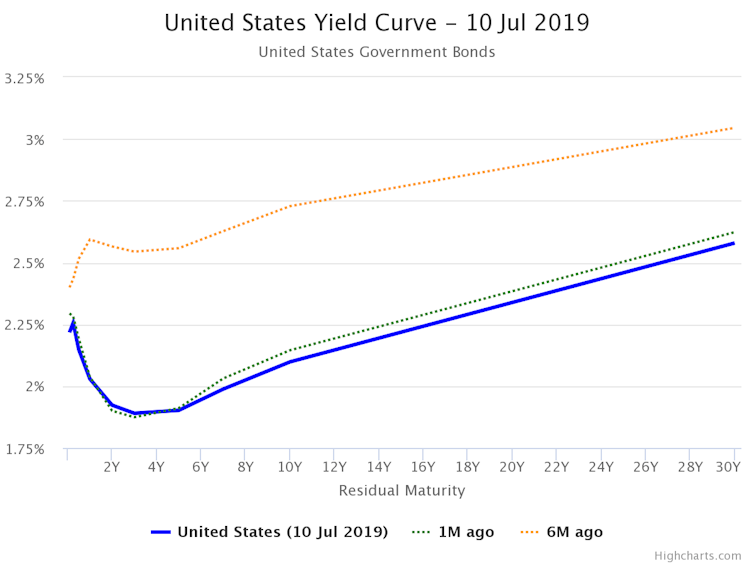

Usually, interest rates on long-term bonds are higher than interest rates on short-term bonds, leading to an upward sloping yield curve. This is because investors need to be compensated for the extra risk they bear when investing in long-term securities.

But interest rates are also determined by expectations. During economic booms, interest rates usually tend to rise. If investors expect interest rates to be higher in the future, then this will be reflected in long-term interest rates since this is simply an average of the expected path of future short-term interest rates.

Alternatively, if investors expect interest rates to fall in the future, long-term interest rates might already fall below short-term interest rates right now. In that case, the so-called yield curve inverts and is downward sloping.

Accurate predictor

Historically, an inverted yield curve has been one of the most accurate recession predictors. Low interest rates tend to be an indicator of low growth prospects and low inflation expectations – both signs of an upcoming economic downturn.

If the yield curve slopes down, investors therefore usually expect a slowing economy. It might also indicate that investors expect the central bank to lower rates in the future in order to prevent an upcoming recession.

Central banks have a history though of reacting far too timidly to upcoming economic troubles. To paraphrase the economist Rüdiger Dornbusch: “Expansions don’t die of old age, every single one of them was murdered by the Federal Reserve.” The Fed in the US and other central banks have historically found themselves behind the curve and tend to do too little too late, as was the case during the Great Recession that started in 2008.

Yield curves have now inverted in the US, in Australia, Canada, and a number of other advanced economies. Even in countries where short-term rates are already at zero, like in Japan and Germany, long-term rates have fallen into more negative territory. This has led to the bizarre situation where investors basically pay those countries a premium for holding their government bonds.

While an inverted yield curve does not guarantee a future economic downturn, the economic outlook has worsened substantially in recent months. Some economists though have suggested the yield curve inversion is not an accurate predictor of an upcoming recession anymore. They reason that measures by central banks and other economic fundamentals make the current yield curve inversion benign.

However, as a rule of thumb, we should be extremely wary of the idea that “this time is different”, when history tells us it usually is not. Indeed, similar stories were told just before the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s and before the housing bubble collapsed a few years later.

In fact, Nobel laureate Paul Krugman suggests that the current yield curve inversion is actually much more dangerous than in the past because interest rates are depressed and stuck at historically low levels across the globe. In the past, the Fed has cut rates by some 5% or more in order to fight an upcoming recession. But this is not an option this time around, since interest rates are already so low in most advanced economies.

This is why the economist Larry Summers argues that the Fed should cut interest rates by at least 0.5% immediately, as recession insurance to boost the economy before it’s too late.

Both the European Central Bank and the Fed have monetary policy meetings at the end of this month. Investors are anticipating that both will cut interest rates in order to fight the recent weak economic data. In fact, these interest rate cuts are already priced into financial markets, which is one of the reasons for why the yield curve has inverted globally.

ECB president Mario Draghi also hinted at a research conference that the ECB is willing to resume its quantitative easing stimulus programme if the eurozone’s economic data deteriorates further. And the ECB’s new chief economist Phillip Lane recently said that the ECB can cut its benchmark rate – already at -0.4% – into even deeper negative territory.

The world’s two major central banks are therefore expected to add new rounds of stimulus very soon, despite global interest rates still being depressed at historically low levels. While these policies are worrisome to some, this kind of action is arguably the only thing that has kept the global economy afloat in recent years. Stay tuned for further central bank action – we need it to prevent another recession.![]()

Julius Probst, Doctoral Researcher in Economic History, Lund University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.