Welcome to the new Meghalayan age – here's how it fits with the rest of Earth's geologic history

Steve Petsch, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Jurassic, Pleistocene, Precambrian. The named times in Earth’s history might inspire mental images of dinosaurs, trilobites or other enigmatic animals unlike anything in our modern world.

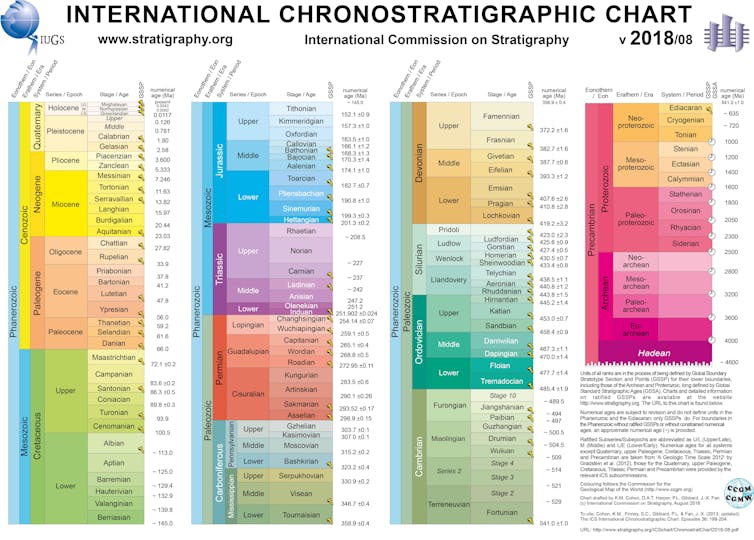

Labels like these are part of a system scientists use to divide up Earth’s 4.6 billion year history. The biggest divisions are eons which split into eras, which break into periods, which divide into epochs and then all the way down to ages.

Officially, we’re living in the Holocene epoch. Informally, people talk about our current age as the Anthropocene, melding humans with the lingo of geologic time. And now, there’s a new age with a new name – the Meghalayan. So how did the custom of dividing and categorizing time get started, and who gets to decide when there is a new age, epoch or era?

Before the ages, naming the rocks

The geologic time scale was not entirely intentional, at least at its start. In the early 1800s, geologists began to create maps and descriptions showing where different types of rocks occurred throughout western Europe.

Some of this was driven by natural curiosity. The Triassic is named because the same three-part layering – carbonate-rich shale on top of fossil-rich limestone on top of red sandstone – was found throughout western Europe. To European scientists, this configuration seemed common enough to warrant a name.

Some labeling emerged from economic motivations. If a particular type of sandstone or limestone or coal proved useful, then people wanted to know where else to put a quarry or mine to find the same rock.

The study of how rocks are layered and organized became formalized as stratigraphy. To assign a name to a particular rock, stratigraphers put criteria in place. There had to be a location where the archetype of that rock could be found. There should be a widespread geographic distribution, as for the Triassic. There might be signature fossils that only occur in that rock, or are not found in younger rocks (suggesting an extinction) or older rocks (telling us when a new species developed).

Names for the divisions of the rock record drew from where those rocks were first or best described – Devonian rocks in Devonshire, Cambrian rocks in Wales (Cambria, as the Romans called the region) – or from obvious characteristics. Cretaceous rocks in Europe are full of fossils that provide a rich source of chalk. Carboniferous rocks around the world include important coal resources.

Rocks equal time

The big mental leap came in connecting rocks with time – those Devonian rocks were formed during what came to be called Devonian time. That’s how geologic time became a convenient shorthand for major events and changes in life’s history on Earth. The Cretaceous is not just chalk. It’s a time when conditions were just right for the seas to be filled with huge populations of plankton – whose bodies sank to the ocean floor and eventually formed chalk when they died.

What began as a system to distinguish different rocks in western Europe has grown into a formalized, sophisticated and systematic way of thinking about life and time and the ways these are recorded in rocks.

The history of Earth’s atmosphere is one example. Invisible chemical proxies created by ancient organisms and preserved in sedimentary rocks record the rises and falls in oxygen and carbon dioxide over the past 600 million years. These coincide with events along the geologic timescale such as major mass extinctions, the evolution of land plants and the assembly and breakup of supercontinents.

Be it fossils or minerals or minute chemical signatures, the stratigraphic records reveals the interplay between life, earth and environment through time.

Defining the Meghalayan Age

Scientists still continue to refine the geologic timescale. This summer brought the official naming of a new age: the Meghalayan.

Numerous climate records show that Earth faced an abrupt shift towards a cooler and drier climate 4,200 years ago. A team led by stratigrapher and climate scientist Mike Walker proposed that this was a significant and global-scale event, best represented by climate signals found in a stalagmite from Mawmluh Cave in Meghalaya state, in northeast India.

The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) and its parent body, the International Union of Geological Sciences, vote on and ratify such proposals. ICS is in effect the official keeper of the geologic time scale. When a new time division is approved, as in the case of the Meghalayan, ICS sets the official description and adds that new detail to the geologic time scale.

All rocks younger than 4,200 years are now part of the Meghalayan Stage. Time since 4,200 years ago is in the Meghalayan Age. But there is a lot to unpack in these details.

Splitting up the Holocene

As of July 2018, the Holocene – the most recent epoch of time spanning from 11,700 years ago to the present – is divided into three ages: the Greenlandian, the Northgrippian and the Meghalayan.

Those first two are unusual because their type localities are not rocks. Instead, they’re layers of ice deep within the Greenland Ice Sheet. Both are defined by major, global-scale environmental change: warming in the case of the Greenlandian and ripple effects of melting ice sheets for the Northgrippian.

The Meghalayan, too, is unusual, and not just for its first-ever use of a stalagmite as the rock that defines the archetype. The global-scale climate change that defines the beginning of the Meghalayan coincides with a period of ongoing migration and collapse of many early human civilizations around the globe. For the first time, our stratigraphy has been defined at least in part by effects on human activities.

What about the Anthropocene?

Which brings us to the idea of an Anthropocene – a proposed division of geologic time defined by signs of human activities in the geologic record. If human activities can be associated with divisions of geologic time – as was done for the Meghalayan – and we define geologic time based on various characteristics in rocks, then what to make of the inescapable imprint of human activities in the rock record?

There are good arguments to be made both for and against an Anthropocene.

Human beings have clearly altered landscapes through deforestation, agriculture and industrialization, which among other things have accelerated erosion and sediment accumulation. Plastics are accumulating in our oceans and biosphere, leaving a global-scale marker of these synthetic materials in soils and sediments. People are causing high extinction rates and rapid changes in where species are found around the world. And of course burning fossil fuels and human-induced climate change leave signatures in sediment records worldwide.

But to date, the International Commission on Stratigraphy has not approved the designation of an Anthropocene. One challenge is agreeing on when the Anthropocene should begin. While things such as plastics or carbon dioxide from fossil fuels are geologically recent, human impacts on landscapes, biodiversity and biogeography may extend back thousands of years. It is very hard to pinpoint the first moment in time when our species began to affect the Earth.

The new divisions of the Holocene also cut into the available time for an Anthropocene. The Meghalayan begins 4,200 years ago and continues to the present. Simply put, there is no time left over in the Holocene where we could put an Anthropocene.

For the Anthropocene to be included in the formal geologic time scale, stratigraphers will need to argue that its onset was global in scale, simultaneous around the world and significant in its imprint on the geologic record.

Or maybe these types of formal requirements no longer apply. As scientists recognize that humans are now part of stratigraphy, perhaps we need to rethink our criteria in a way that separates geologic time from human time.

This article has been updated to correct the order of labeling in geologic time.![]()

Steve Petsch, Associate Professor of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.